Полная версия

You: Staying Young: Make Your RealAge Younger and Live Up to 35% Longer

4. Ageing Is Not About Individual Problems but Compounded Ones

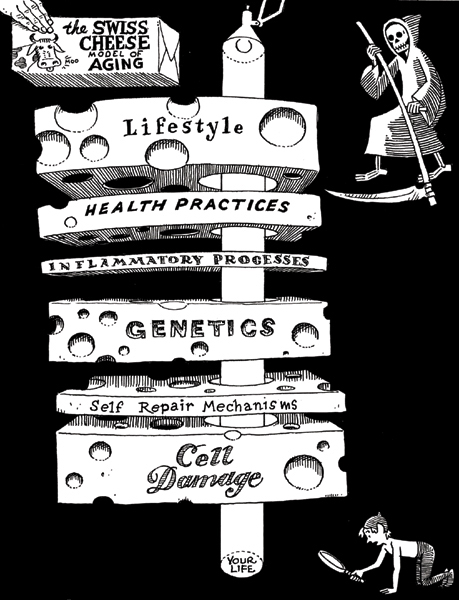

Spend any time at a deli counter, and you know that Swiss cheese has two different looks. Big holes or small holes, all in random order and patterns. A good way to think about ageing is to imagine yourself looking through a dozen slices of stacked-up Swiss cheese (see Figure Intro 2). If the holes are small and the slices are thick, you can’t see through the stack. Now pretend that each of these Swiss cheese slices represents a layer of protection that your body provides to prevent ageing. People who are vibrant and strong may have small holes in their system – stuff that lets through a few problems, but nothing too major. Maybe they’ve got a little hole in their slice of heart health, and a few little holes in their slice of brain health, and a medium-sized hole in their slice of chromosome health. Nothing major lets you see through the stack.

FACTOID

Currently, there are more than six thousand centenarians in the UK. This number is expected to increase to forty thousand in 30 years’ time. (The Guardian, 18 January 2006)

As ageing takes effect, however, those holes can get a little bigger, or the cheese can get a little thinner. When big holes from one slice perfectly align with big holes from another slice, then, in effect, you’ve got big problems. That’s a little bit what ageing is like: the small problems may not have a big effect here and there, but when they grow, and when they interact with other problems, then you’ve created what we like to call a (cue scary orchestra music) web of causality. That’s when seemingly small health problems spiral into bigger ones – all possibly triggered by several different causes.

Figure Intro 2 Cheese Doodle Each layer of resilience we have against ageing is like a slice of cheese. The differences in hole size, number of holes and thickness of slices describe how we protect ourselves against ageing.

5. Ageing Is Reversible – All You Need Is a Nudge

Most people think ageing is a landslide of a process, that we’re destined to use walkers and hearing aids and thick glasses no matter what. And while we’re not saying that you will absolutely avoid all the bumps (big and small) along the way, we are saying that ageing isn’t as inevitable as a morning trip to the toilet.

What you will learn in this book is how to nudge your systems so that they work in your favour to create leverage points in life. And the great thing is that it’s never too early or too late to start making these changes. You don’t need a complete overhaul, because, frankly, your body is a pretty fine piece of machinery. What you’ll ultimately do is find and fix your own personal weak links – the things that make you most vulnerable to the effects of ageing. The cumulative effect of those nudges, though not major from a behavioural or even a biological perspective, can be huge when it comes to increasing the length and quality of your life.

The truth about ageing is that you – right now – have the ability to live 35 percent longer than expected (today’s life expectancy is seventy-five for men and eighty for women) with a greater quality of life and without frailty. That means it’s reasonable to say that you can get to one hundred or beyond and enjoy a good quality of life along the way. While relying on the talents, skills and knowledge of others may get you out of a medical jam, what you really want is to avoid it in the first place. Restricting calories, increasing your strength and getting quality sleep are three of nature’s best anti-ageing medicines. Together, these activities – as well as the other actions we recommend – control 70 percent of how well you age. Wouldn’t you want to hold the power of your future in your hands, rather than put it in someone else’s?

Just because you’ve made mistakes in the past doesn’t mean you can’t reverse them. Even if you’ve had burgers for breakfast or fried your brain cells with stress, you’re not necessarily destined to wear elasticated waistbands and forget birthdays. No matter what kind of life you’ve already led, ageing is reversible: you can have a do-over if you want it. If you perform a good habit for three years, the effect on your body is as if you’ve done it your entire life. Even better, within three months of changing a behaviour, you can start to measure a difference in your life expectancy.

As we said, ageing is inevitable, but the rate of ageing is not. Consider this fact: only 10 percent of people are classified as frail when they’re in their seventies. By the time people reach one hundred, almost 100 percent are considered frail. What we’re trying to do is make sure that percentage stays lower for longer. We want you to feel as good at the end of the race as you do at the start.

Our goal here is to ensure that you have a high quality of life until whatever time – forgive our bluntness – you drop dead. That’s the ideal scenario, right? Nobody wants to spend their golden years on diets of jelly, suffering from bedsores, or not remembering the previous nine decades. You want to feel like you’re thirty even when you’re eighty. You want to have the wisdom of a grandparent without feeling like one. So our goal isn’t to get you to 120 – unless those 120 years come with quality.

After all, living longer shouldn’t be about “taking longer to die”, which is what so many people think it means. It should be about enjoying every moment of a longer life – and taking longer to live.

You want to live long and live well. You want to feel alive while you’re living.

You don’t want to grow old. You want to stay young.

This is the way.

Now get on with it.

Figure Intro 3 Major Ager Crib Sheet The scale of ageing balances between repair and damage mechanisms, and we have seven Major Agers in each category weighing in on whether you are growing younger or older. The higher up the Major Ager is listed on our scales, the more it acts within our cells.

Major Ager Bad Genes & Short Telomeres How Genetics Influences Ageing – and You Control Your Genes

As we get older, it’s easier and easier to pass the blame for our own health problems on to other people. Recently diagnosed with high cholesterol? Aha, three grandparents and two great-uncles all died of heart disease. Accidentally put the ketchup in the freezer the other day? Oh yes, Aunt Matilda had a touch of dementia. Battling a weight problem for most of your life? Yup, Dad and his brothers believed in the three food groups of cheese ravioli, meat sauce, and multiple helpings.

In fact, many of us buy into a very similar theory of ageing: we’re born with our health destiny. That is, our genes – the chromosomal alphabet soup that includes ingredients from our parents, their parents and so on – are primarily responsible for determining whether we’ll get heart disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s or any of the other diseases or conditions that can turn a grade-A quality of life to spoiled minced beef.

But that’s simply not the way ageing works. Your genes are important, especially when it comes to one of the most powerful age-related problems: memory loss. Your genetic destiny, however, is not inevitable.

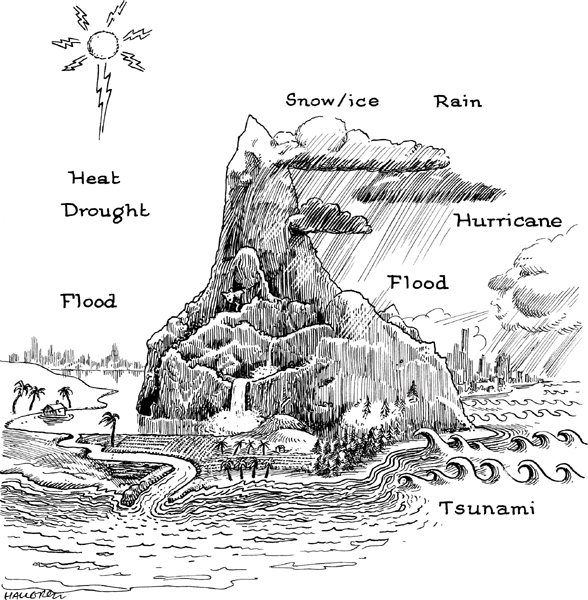

What do we mean by that? Think back to the city that we outlined for you in the introduction, and consider your genes as the physical location of that city. Some characteristics you simply can’t change. Chicago is windy, Manchester is rainy, San Francisco is built on fault lines, Cape Hatteras is in the path of tropical storms. A city’s location serves the same function as your body’s genes. Your genetic traits make you more or less predisposed to health-related windstorms, snowstorms, earthquakes and hurricanes. But just as you can modify cities to adjust to natural geography and natural occurrences, you can also protect yourself from abnormalities in your genes if you’re unhappy with how you’ve been genetically programmed.

FACTOID

The telomeres of people who feel more stressed are almost 50 percent shorter than people who say they’re less stressed. Since scientists have a rough idea what the average telomere length is for a specific age, they can estimate how much older the higher-stress group is biologically: a whopping nine to seventeen years. Just by thinking they were ageing faster, they actually aged faster.

When it comes to your body, here’s what we know, primarily through studies of identical twins: your longevity is based one-quarter on your genetics and three-quarters on your behaviours and lifestyle choices. It’s not about what genes you have but how you express them. Genes work by manufacturing proteins, but whether or not a specific gene is turned on or off is largely under your control.

Think of the ability to manipulate your genes as developing a set of city building codes to adapt to the circumstances you’re in. It would be like a coastal town requiring houses to be built on stilts to protect against surging tides or office buildings in San Francisco using earthquake-resistant materials to better protect against an architectural crumble. You adapt and adjust to deal with whatever nature throws your way. That’s the way your body works. As the mayor of your physiological city, you can create different codes to mitigate the effects of the genes you’ve been dealt. For example, exercise isn’t good for you just because it helps burn fat and assists with bikini satisfaction, but it can also alter the expression of your genetic codes to decrease your risk of getting cancer. That means you do have some control over how your genes manifest themselves in your body and how they control the rate – and way – that you age.

Figure A.1 Geography Lesson Location is location, just as genes are genes. But you can manage the city’s geographic area and climate by being innovative. After all, great cities arise from very different geographies.

Maybe you’ve been dealt a bad hand of genetics, but that doesn’t mean you can’t exchange a few cards, or at least change how you play them. Another way to think about your genetic inheritance: it’s stored information, the factory-installed info that comes with your biological system. You have the power – with your behavioural software – to alter that information along the way. But if you don’t take any action, then the stored information is what dictates how those genes play out.

Which of Your Genes Is Turned On?

Controlling your genetics can help you avoid the major age-related diseases and improve the chances that you’ll spend more time with your grandkids than you will in doctors’ waiting rooms reading large-print magazines that are three years old.

If you remember our Swiss cheese model, it makes sense: by fixing one thing about your body – like adding a daily thirty-minute walk – you’ll end up (perhaps unintentionally) fixing many others along the way, so that the holes of ageing don’t line up and cause total system failure. And by making small changes, you’ll reach that goal of adding years and quality to your life.

So how do you change the function of your genes? One way is through the rebuilding of chromosomes. Your chromosomes, the little rascals, have small substances on the ends called telomeres (see Figure A.2). Think of them as being like those little plastic tips of shoelaces (which are called aglets, in case you want to show off in your next Scrabble competition). Every time a cell reproduces, that telomere gets a little shorter, just as the shoelace tip wears off with time. Once the protective covering on the tip is gone, your DNA and shoelace begin to fray and are much harder to use. That’s what causes cells to stop dividing and growing and replenishing your body. The cell realizes that it is no longer helping the body and commits suicide (that’s called apoptosis), which can contribute to age-related conditions. But your body also has a protein – called telomerase – that automatically replenishes and rebuilds the ends of the chromosomes to keep cells (and you) healthy. However, lots of cells in your body don’t have telomerase, meaning that many of them have a reproduction limit – thus putting a cap on how well your systems can be replenished. (Telomerase, by the way, is overactive in 85 percent of cancers. That makes sense, right? Rebuilding the aglet that allows cells to divide helps those cancer cells reproduce and spread.)

Figure A.2 A Good Tip Your chromosomes have small caps on the ends called telomeres, which are like those little plastic tips on shoelaces. Every time a cell reproduces, that telomere gets a little shorter, just as the shoelace tip wears off with time. You need a substance called telomerase to rebuild the cap.

The amount of telomerase depends on your genetics, but we’re now starting to see that we can influence the size of those little tips, the telomeres. For example, researchers have found that mothers with chronically ill children have shortened telomeres, indicating that chronic stress can have a huge influence on how cells divide – or fail to. The implication is that if you can reduce the effects that stress has on you, through such techniques as meditation, you can increase your chance of rebuilding the telomeres and decrease the odds of having your cells die and contribute to age-related problems.

Yes, you’re stuck with the genes you were given, just as you’re stuck with the decisions your parents made about where you grew up, and you can’t return your genes for a complete refund. You can, however, change the way they function. We’re starting to uncover more and more ways that you can change how your genes function, which we’ll detail in the following chapter about your memory. For example, just ten minutes of walking turns on a gene that decreases the rate of cancer growth, and resveratrol (the ingredient found in red wine) turns on a gene that slows or stops a dangerous inflammatory process that happens inside your body. And in the very near future, we’re going to be able to develop medicines tailored to individuals whose genes work differently from others’.

Because each of us has a unique genetic fingerprint, the detection, prevention and treatment of diseases can be difficult. But as we start to unlock the ways that we and modern medicine can dramatically manipulate our genes, we’re going to start seeing how we can make our genes work for us, not against us. Perhaps the best example of how genes affect us is our memory, which is goal one – in part so you can remember the rest.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.