Полная версия

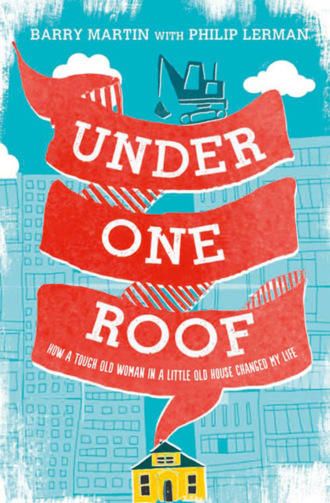

Under One Roof: How a Tough Old Woman in a Little Old House Changed My Life

For Edith

and for my dad,

William M. Martin Jr.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

I finally moved the cookies.

They were Walkers Pure Butter Shortbread cookies, the only brand of cookies Edith liked. They came from Scotland, and when you would eat them it was like you just ate a tab of butter. I remember she sent me to the store for cookies once, and they didn’t have her brand, so I brought not one, not two, but three others home. She took a bite of each one, and pushed them back at me. “All yours,” she snapped, staring up at me with those piercing blue eyes. “Not mine.”

It was always a battle of wills with Edith.

I eventually hunted down the Walkers at the old Ballard market. When I brought them home, she took one bite and said, “Well, that was worth waiting for, don’t you think?” Like she was a schoolteacher who’d just taught her problem student a simple lesson. There I was, a fifty-year-old man, a person with a position of responsibility, and she still made me feel like a kid, every single time.

After she died, and for the longest time after that, I couldn’t touch anything in her house. Like that box of cookies. It just sat there on the shelf next to the stove in that cramped kitchen, staring down at me, as if it was daring me to throw it out. Like it knew I wouldn’t. I was going to take the cookies over to the trailer at the construction site and let the boys have them. I brought the box to the door twice, at least, and set it down, and thought, well, I’ll get it when I go out. But when I was leaving, I just couldn’t take the cookies. I couldn’t leave them sitting by the door, either, because Edith would hate it if anything was out of place. So I’d pick them up and put them back on the shelf, right where they belonged, lengthwise, with the name “Walkers” showing on a bed of Scottish plaid.

I guess I just wasn’t ready.

I’m sitting in her house right now for what will probably be the last time, and looking at all this stuff, and wondering why it has such an effect on me. For the last couple of months, I’ve come over here, trying to pack up her things. There’s just so much. The music alone is going to take half a day. There’s the albums, hundreds of them: Mantovani, for example. Maybe thirty of those. Who the heck has thirty Mantovani albums? And tons of Guy Lombardo. Then all these cassettes on the wall, in a cheap little wooden cassette case that’s sagging in the middle – cassettes of Caruso and Beethoven and Benny Goodman. And CDs. Hundreds and hundreds of CDs. I guess she moved along with the times, up to a point – the albums, then the cassettes, then the CDs. The progression stops there, but still, it’s kind of funny to see so many CDs in a house where everything else feels like it’s straight out of the fifties. Anyway, I’d come here to pack stuff up, then walk around in circles for fifteen minutes, and leave without touching anything.

Even after all this time, whenever I walk in that front door, I expect to see her lying on the couch. I haven’t sat on that couch even once – I can’t bring myself to sit on it, the couch she lay on every day and slept on every night. I think I haven’t moved anything because she was just so particular that everything went back exactly where it was. There are hundreds of little ceramic figurines all over this place – lots of cows, and some little dogs and cats. She loved animals: here’s a ceramic cat at a piano that says “Meow-sic” and a begging dog and a bunch of little ceramic pigs. And back in the kitchen, she had the figurines from the Red Rose tea boxes. I don’t think she even liked the tea all that much, but she loved those little figurines. I read somewhere that Red Rose has given away 300 million of those little toy statues. Sometimes it feels like Edith had half of them.

And if you moved any of her figurines, anywhere in the house, she’d notice and get heartburn. One time my wife and daughter came down here to clean up the house a little, and the next day Edith was so irritated. “Where’s this?” and “What’s that doing over there?” she said to me. I asked her, what does it matter, but that just made her more irritated because she wanted things where they belonged. Maybe it’s because that’s where her mother kept things. Edith had a really strong connection with her mother, and a lot of things changed when her mother died. Or I guess it’s more accurate to say, a lot of things had to stay the same.

I think a lot of people face this when their parent dies. Edith wasn’t my mother, of course, and in a lot of ways I felt more like a parent to her, taking care of her like she was a child, not to put too fine a point on it. I still faced those same issues, though. The difficulty of accepting that she’s really gone. You question yourself: Did I do everything I was supposed to do? I think that until you answer that question, you can’t accept what’s happened. Maybe that’s why I kept everything just where it was, like in a state of suspended animation, while I thought about it.

It was such a strange turn of events that brought me into this little house. There I was, just going to work every day, a project superintendent in charge of building a shopping mall on a lot that was empty except for this one little ramshackle house we had to build around. It wasn’t my fault that there was this struggle between the project and this lady’s house. It’s just the job. The developers were trying to get her to move. She was digging in her heels, insisting that she was going to stay. And there was me, caught in the middle. Everyone thought I was trying to trick her into moving. But the truth was just the opposite. I was doing everything I could to allow her to stay.

So what, you might ask, was I doing over there? What was in it for me?

Good question.

I guess, if you try to dissect the friendship that formed between us – and a lot of people seem to want to do that – you could start with the books.

Over on one wall, next to the couch, there was a whole collection of classic books, like Wuthering Heights and Canterbury Tales and Das Kapital and the poems of Longfellow. They were all dusty, like no one had read them for a long time, but every once in a while she’d quote from them, so I know she read them all, some more than once.

I think that’s one of the things that drew me in. I was fascinated with how much she knew. I guess that’s because I never met anyone who had read as much, who knew as much, as Edith did. It was like meeting someone from another planet. A different kind of intelligence. It just draws you in.

And then, of course, there were the stories. Edith’s stories.

For a guy like me, growing up like I did, you didn’t exactly run into people every day who told you they were Benny Goodman’s cousin. Or who taught Mickey Rooney some dance steps. Or escaped a Nazi concentration camp. Or said they did, anyway.

Here’s exactly what I thought of that, at first:

Wack job.

Not very nice, I know. But that’s where I was at, pure and simple.

But as I started to go over there more often, and heard more and more of the stories – just little bits and pieces of them, just enough to make you wonder – I found myself wanting to hear more. Looking at Edith was a little like looking at those books: a million stories hidden in there. Maybe half of her stories weren’t true. But it was real interesting, just to know they were there.

I was never much of a reader, myself. There weren’t a whole lot of books around my house, growing up. I guess if I was going to school today they would have diagnosed me with attention deficit disorder, because I could never really focus on reading or anything like that. But as it was, I muddled through. I never even watched a lot of movies, to tell you the truth. Take me to a movie theater and I’d be asleep in fifteen minutes. Just couldn’t focus on it. But I did watch a few movies with Edith. She had tons of tapes all around this room as well, all movies from the forties and fifties. Lots of Bette Davis, lots of Sherlock Holmes. A lot of Greta Garbo, too: Grand Hotel, Anna Christie, Ninotchka. Somebody told me they thought Edith was a little like Garbo, holed up here in this little 106-year-old house in a shabby section of Seattle – but they had it wrong.

Edith didn’t want to be alone.

2

I was nervous, that first day on the job, walking up to her house. I’d heard so much already. At first I hadn’t been paying too much attention. I’m not that much of a reader, as I mentioned, and I hadn’t seen any of the articles in the paper, or heard about how the local newspaper reporters were all scared of Edith because she’d chase them away whenever they got within ten feet of her. In fact, when I got the job as construction superintendent for the shopping mall project, my wife asked me, “Oh, is that the one where the old lady won’t move?” And I said no, because I was sure I would have heard about it.

But when I mentioned it to the guys I worked for, they told me that yes, they had this stubborn old lady, like a little bulldog with wire-framed glasses, holding up the whole works. They’d gotten every other inch of the property they wanted, basically a city block square, except for this one little ramshackle house. Now they were having to build around it. And if anyone tried to talk to her, she’d more likely bite their head off than give them the time of day.

The first time I looked at the architect’s drawing, I saw the tiny rectangle that was cut out where Edith’s house stood. Later, the owners of the project and I talked it over, and we decided to put some steel embeds in the side walls facing Edith’s house, big galvanized steel plates with metal studs that go back and tie into the concrete. If she wound up selling, we could tear down her house and build across by welding beams to those embeds – basically filling in the little rectangle. And if she didn’t, well, I had perfectly good plans for building around her. To me, it was a construction job, and a pretty big one at that. I didn’t really care one way or the other.

The wheels had all got set in motion about a year earlier, back in the spring of 2005. I had worked for one construction company for almost ten years. For a while, there was a ton of work. Up here in Seattle, we really reaped the benefit of the dot-com boom even more than people know. I was a project superintendent, meaning I was basically in charge of all the people and subcontractors on a big project, such as an office building. It was the kind of thing that you figured, well, this is what my life is gonna be, and I’ll retire with this company. And you feel pretty good about it.

Then the dot-coms all went down and things got strange. There was a glut of office space, so the banks started pulling the plug on any project with office space in it. There just wasn’t enough work to go around. The company I worked for finally went out of business. I went to work for another fellow, building assisted-living facilities.

I wouldn’t know until later how ironic that was. When it became my whole life’s work just to keep one old lady out of them.

The boss was a good person to work for; the firm was small, and I was given a lot of autonomy, so it was easy to get things done. I was happy just to have landed on my feet, given how tough things were. But that spring, all the guys from my old company, the one that went out of business, got involved with another firm, called Ledcor. The owner of the old company came to run Ledcor’s Seattle office, and the old operations manager came on board, and the business-development guy, and their best project manager. Then they called me to come join the party.

I loved working with that crew. They were nice guys, and they really cared about you. They had this project they wanted me to do, and – not to put too fine a point on it – they started hounding me. Hounding me in a nice way, of course. But I knew what they were doing. The first calls came from the project manager, a great guy named Roger Wagner. Roger wouldn’t tell me too much about the job – just that it involved a whole city block, and that once that was done, there were one or two other blocks, and by the way, this Ledcor was a great place to work.

See, that’s how it works: he’s sticking the bait out there and waiting to see how hard you’re sniffing. Then if you’re interested, he’ll feed you the bait and reel you in. I knew what he was doing – and he knew that I knew – so it was all very jovial. But at the same time, I was a little intrigued, because you never know what’s going to happen tomorrow so you never slam the door on anything.

The next one to call me was the operations manager. He was also giving it the soft sell, because nobody wanted to seem too eager. So we all went around it for a month or two, until they finally gave me the are-you-in-or-are-you-out call.

It was a tough decision. These guys were like family to me, but I hated leaving the job I had. I don’t like leaving things without a reason. I need to be able to say, well, this bothers me or that bugs me. But there was nothing wrong with where I was. I looked for a reason to justify the move, and all I could come up with was, well, these guys have a better retirement program or a better bonus-potential program, or they’re large enough that there is room for me to grow. But I knew that at that point I was just making excuses to do what I already knew I wanted to do.

So I said, I’m in.

The project was to build a shopping mall. A developer, the Bridge Group, had purchased most of a city block in Ballard, a nice, sleepy waterfront neighborhood just over a short bridge from downtown Seattle. But the project got stalled off just as I came on board, so they had me working on another project in the meantime. That Christmas, while I was still waiting to get started down in Ballard, a columnist for The Seattle Times apparently wrote about an odd phenomenon that went on down near the site. I didn’t read about it at the time, but I heard about it later: At night, after the bars closed, lots of people with no place else to go would park their cars on the side streets, and kind of live in them. The columnist, a guy named Danny Westneat, wrote that one night he counted forty-one live-in vehicles parked in a couple-block area – right in the neighborhood where I was going to be building the mall.

In the article he quoted Edith, saying she thought that maybe two hundred or three hundred of these itinerants camped out in this rolling car colony on the weekends. You’d think the locals would be pretty furious that the cops were letting this go on, but her attitude was “What can you do? They don’t have any money, so where can they go? The way I see it, if they don’t bother me, I don’t bother them.” Seemed like a pretty philosophical approach. I didn’t see that article until much later, but when somebody did show it to me, I was kind of surprised – you don’t expect someone with a reputation for being so ornery and crotchety to be so accepting of stuff like that.

Sometimes people aren’t who you think they are.

It was spring of 2006 when most of the permits cleared and we could finally get rolling. I got down there early that first day, to do what I always do when I start a job. I began by going around to all the neighbors on the surrounding streets, introducing myself to people, making sure they had my cell phone number in case there were any problems. I always feel like it’s good to get that up front first. You can’t pretend to do a big job like this right down the block from someone and not have them notice, or act like you’re never gonna cause them a problem. But you can let them know you care enough to hear about what you’re doing that’s annoying folks, and you’re willing to meet them halfway. I feel like it’s my responsibility. If someone was doing that to me, I’d expect the same.

The first day of breaking ground still gets to me after all these years of working construction. It’s that sense of anticipation you feel on the first day of school – excited and nervous all at the same time. Especially when you break ground in springtime. There’s something about that fresh spring air that gets in your blood, and it was getting to me as I walked the streets of Ballard that morning, although, to be honest, Edith’s block was no bed of roses. Her street still had a lot of those transients living in cars, and you could see a few of them sleeping in their dilapidated old vehicles that morning. They had a tendency to clean out the nearby Dumpsters and then toss whatever garbage they had right outside the cars, and use the weeds for their Porta-Potty, so it wasn’t the most savory atmosphere you could imagine. Pretty disgusting, actually.

But as I approached Edith’s house, I got a strong whiff of fresh-mown grass, and it took me back to when I was a kid, mowing lawns for quarters. Same thing happens to me in the fall, the smell of leaves and the snap in the air. It takes me back to when I’d go hunting with my dad. Those smells bring you back to happy times, and they kind of bring the happiness back with them. It’s a good feeling.

In the springtime I always think I’m smelling the bubble gum that came with baseball cards. I was probably imagining things, but that’s what it felt like as I approached Edith’s front gate. For just a moment, you feel like a man and a child all at the same time.

Most of the sidewalk on Edith’s block is overgrown with blackberry bushes, but they stop at her property line. Her yard is like a little clearing in that jungle. Within that clearing, Edith’s house looks like something out of a storybook. A compact building, two floors, plus a basement that peeks up out of the ground, the whole thing maybe twenty feet wide. It’s set about ten feet back from the sidewalk and the ground slopes down toward the house so the foundation is a good three feet lower than the street in front of it, making the house seem even smaller than it is. Or as if the house is crouching a few feet from the street, tired from too many years of trying to stand up straight.

There’s a tiny entranceway in front, with an arched opening. It looks like the miniature house on the front of a Swiss cuckoo clock, and you half expect a little wooden soldier to come sliding out of it every hour on the hour. There’s a small patch of grass, which Edith kept neat and tidy. It’s somewhat overgrown with dandelions now, but when I first walked past the house, it was one of the first things I noticed: how tidy the lawn was. It brightened up the neighborhood: a beautiful oasis in that ugly place, with irises planted all around it. It felt welcoming, and drew your eye away from all that urban decay. It made me feel good to see someone who, from outside appearances anyway, was happy with how she had things, especially when what she had wasn’t much. Most people complain about what they don’t have; here was someone making the most of what she did have.

Edith was tending her garden that morning. Kneeling down like that, it looked like she was praying, or looking for something she’d lost. My first reaction was one of relief. She reminded me of my great-grandma, a small, sweet, meek-looking lady, like someone in a storybook who would have a mouse for a pet. I was still a little leery, though, because I didn’t know how she was handling the news about the construction, and because of what the guys had told me about her.

“Hi, I’m Barry Martin,” I said. “I’m going to be building this project around you.” I braced for the worst.

“Well, I’m pleased to meet you,” she said, rising slowly, like she was unfolding her limbs one by one. “I’m Edith Wilson Macefield.”

A concrete truck from the Salmon Bay Concrete Plant a half-block down from her house roared past us, keeping us from talking for a moment. We sized each other up in silence, waiting for the truck to pass. Even standing up, Edith was a little stooped over, with a hunch to her back, and hazel-blue eyes that didn’t quite both look at you at the same time. She had to pick one eye to fix on you, but she made up for it by looking at you straight and hard, and not letting go of your gaze once she had it. She was a thin woman with white hair and a wide face, and looked like the kind of person who cared more about her appearance than you might expect of someone that age, especially someone seemingly so isolated. She was wearing a blue knit sweater and a pair of slacks and some garden gloves, and she pulled off one glove, walked over, and shook my hand. Even though she was small and frail, her handshake seemed strong and confident. I was relieved – the anger I’d expected from her hadn’t materialized. But I felt a little sad, too, to see this old woman, apparently living so alone.

“Well, nice to meet you, Miss Macefield,” I said. The concrete truck had passed, and the rumble of cars coming over the bridge had stopped for the moment; all of a sudden the air was still and silent, the way it gets on a warm spring day. You could hear someone mowing a lawn a few blocks away, it was that quiet.

I had introduced myself to just about everybody who would be affected by the project, but as much as I knew this was all just part of the job, this particular introduction seemed different – I mean, we were going to build a shopping mall all around this lady’s house. I couldn’t imagine what that would be like. Or actually, I could. A hell of a lot of noise and dirt and debris and destruction. I had the urge to sugarcoat it a bit, to try to make it seem less disturbing than it was likely to be; but one look at Edith and you knew: this was not a lady who took her medicine with a spoonful of sugar.

“Miss Macefield, I just want to let you know we’re going to be making a whole lot of noise and creating a big mess. There’s no way around that. But if you ever need anything, or have any problems, here’s my number. Don’t hesitate to call.”

“Well, that’s very nice of you,” she said, taking my card, holding it up close to one eye, then tucking it into a front pocket of her slacks. “I’m glad to have you here. It’ll be nice to have a little company.”

As we talked, she picked up a bag of birdseed and started spreading it on the sidewalk.

“Like to feed the birds, do you?” I asked.

“Every morning,” she replied. “I’m running late today. Had a little trouble with insomnia last night, so then I fell asleep and woke up a little late.”

“Well,” I said, “let us know if you need anything.”

“Thank you,” she said, and then, as I walked away, I heard over my shoulder: “You can call me Edith.”

I heard the rumble of the cars across the bridge nearby. I thought I got a whiff of that baseball-card bubble gum, too. I looked back and saw Edith struggle to get down to her knees, until her whole form was tucked behind the chain-link fence that faced her house, as though she had revealed just a little bit of herself, just for a moment, and now she was going back into hiding.

It’s funny how the most momentous conversations of your life – or the ones that turn out to be the most momentous – can seem, in the moment they happen, so mundane.