Полная версия

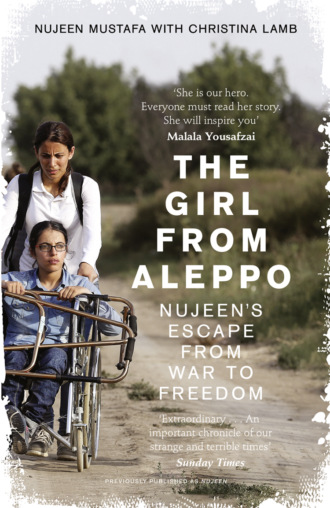

The Girl From Aleppo: Nujeen’s Escape From War to Freedom

Kurds together always tell stories. Our most famous story is a Kurdish Romeo and Juliet called Mem and Zin. It’s about an island ruled by a prince with two beautiful sisters he keeps locked up, one of whom he calls Zin. One day Zin and her sister escape to go to a festival disguised as men and meet two handsome musketeers, one of whom is Mem. The two pairs of sisters and musketeers fall in love and a lot of things happen, but basically Mem is imprisoned, then killed, and Zin dies of grief at her lover’s grave. Even after death they are kept apart when a thorn bush springs up between them. The story starts by saying, ‘If only there were harmony among us, if we were to obey a single one of us, he would reduce to vassalage Turks, Arabs and Persians, all of them,’ and many Kurds say it symbolizes our struggle for a homeland. Mem represents the Kurdish people and Zin the Kurdish country, separated by unfortunate circumstances. Some people believe it’s true and there is even a grave you can visit.

I grew up hearing this story but I don’t really like it. It’s quite long and I don’t think it’s realistic at all. Actually I preferred Beauty and the Beast, because that’s based on something good, loving someone from the inside, for their personality, not the outside.

Before he got old and tired and stopped working and spent all his time smoking and grumbling about his sons not going to mosque, my father Yaba was a sheep and goat trader. He had about 60 acres of land, where he kept sheep and goats like his father before him going right back to my seventh grandfather, who had camels and sheep.

My elder siblings tell me that when he started he would buy just one goat a week in the market on Saturday then sell it elsewhere the following week for a small profit, but over time he had a flock of about 200. I guess selling sheep didn’t make much money, as our house was just two rooms and a courtyard with a small kitchen which was a squash for so many people. But my eldest brother Shiar sent money, so we built another room where Ayee kept her sewing machine, which I played with when no one was looking. I slept there with her unless we had guests.

Shiar lives in Germany and is a film director who made a movie called Walking about a crazy old man who walks a lot in a Kurdish village in southern Turkey. The man makes friends with a poor boy who sells chewing gum, then their area gets taken over by the military. The film caused an outcry in Turkey because the old Kurdish man slaps a Turkish army officer, which some people protested shouldn’t be shown – as if they can’t tell the difference between a movie and real life.

I had never met Shiar as he left Syria in 1990 when he was seventeen, long before I was born, to avoid being conscripted and sent to fight in the Gulf War in Iraq – we were friends with the Americans in those days. Syria didn’t want us Kurds to go to its universities or have government jobs but it did want us to fight in their army and join its Ba’ath party. Every schoolchild was supposed to join, but Shiar refused and managed to escape when he and another boy were marched to the party office to be signed up. He had always dreamt of being a movie director, which is strange because when he was growing up our house in Manbij didn’t even have a TV, only a radio, as the religious people didn’t approve. When he was twelve he made his own radio series with some classmates, and he sneaked every opportunity to watch other people’s TVs. Somehow our family raised $4,500 for him to buy a fake Iraqi passport in Damascus, then he flew to Moscow to study. He didn’t stay long in Russia but went to Holland, where he got asylum. There are not many Kurdish film-makers, so he is famous in our community, but we weren’t supposed to mention him as the regime don’t like his films.

Our family tree only shows men, but it didn’t show Shiar in case anyone connected him with us and caused problems. I didn’t understand why it shouldn’t have women. Ayee was illiterate – she had got married to my dad when she was thirteen, which means that by my age today she had already been married four years and had a son. But she made all our clothes and she can tell you where any country in the world is on a map and always remember her way back from anywhere. Also she is good at adding things up, so she knew if the merchants in the bazaar were cheating her. All our family is good at maths except me. My grandfather on my mother’s side had been arrested by the French for having a gun and shared a cell with a learned man who taught him to read, so because of that Ayee wanted us to be educated. My eldest sister Jamila had left school at twelve as girls in our tribe are not supposed to be educated and stayed at home and kept house. But after her, my other sisters – Nahda, Nahra and Nasrine – all went to school, just like the boys, Shiar, Farhad, Mustafa and Bland. We have a Kurdish saying: ‘Male or female, the lion remains a lion.’ Yaba said they could stay for as long as they passed the exams.

Each morning, I sat on the doorstep to watch them go, swinging their schoolbags and chatting with friends. The step was my favourite place to sit, playing with mud and watching people coming and going. Most of all I was waiting for someone in particular – the salep-man. If you haven’t tried it, salep is a kind of smoothie from milk thickened with powdered roots of mountain orchids and flavoured with rosewater or cinnamon, ladled into a cup from a small aluminium cart, and it is delicious. I always knew when the salep-man was coming as the boom-box on his cart broadcast verses from the Koran, not music like other street vendors.

It was lonely when they had all gone, just Yaba smoking and clacking his worry beads if he didn’t go to his sheep. To the right-hand side of the house, between us and our neighbours who were my uncle and cousins, was a tall cypress tree which was dark and scary. And on our roof were always stray cats and street dogs which made me shiver because if they came after me I couldn’t run away. I don’t like dogs, cats or anything that moves fast. There was a family of white cats with orange patches which spat and swore at anyone who came near and I hated them.

The only time I liked our roof was on hot summer nights when we slept up there, the darkness thick around us like a glove and a fresh breeze cooled by the emptiness of the desert. I loved lying on my back and staring up at the stars, so many and so far stretching into the beyond like a glittering walkway. That’s when I first dreamt about being an astronaut, because in space you can float so your legs don’t matter.

The funny thing is you can’t cry in space. Because of zero gravity, if you cry the way you do on earth the tears won’t fall but will gather in your eyes and form a liquid ball and spread into the rest of your face like a strange growth, so be careful.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.