Полная версия

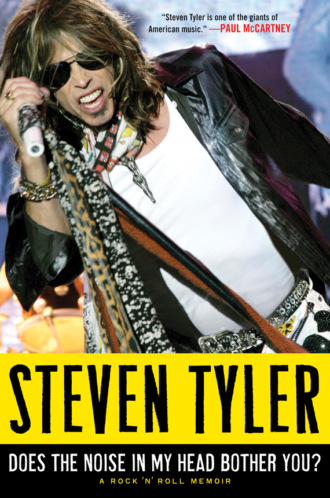

Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: The Autobiography

Where it all began . . . or, why I must love to tour.

My mother’s father—that was another story. He got out of Ukraine by the skin of his teeth. The family owned a horse-breeding ranch. The Germans invaded and machine-gunned the family down in front of my grandfather. “Everyone out of the house!” Bb-r-r-r-r-a-t! They gunned down his mother, father, and sister. He got away by jumping down a well and managed to grab the last steamer to America.

Trow-Rico is where I spent every summer of my life until I was nineteen. On Sundays my family would throw a picnic for the guests. My uncle Ernie would cook steaks and lobsters on the grill, and we’d make potato salad from scratch. We served all the guests—which came to what? eight families, some twenty-odd people—in our heyday. After dinner, while the sun was going down, we’d fill in the trailer with hay, attach it to the back of a ’49 Willys Jeep, and take everybody on a ride all over the property. We also had a common dining room where we served them breakfast and dinner, and guests would do lunch on their own, all for, like, thirty dollars a week. Sometimes six dollars a night. And when the people left, my whole family got pots and pans out of the kitchen and banged them all together—behold the origin of your first be-in!

Summer of 1954 at Trow-Rico. I’m at the top on the left, Lynda is in the straw hat, and Sylvia Fortune, my first girlfriend, is on the right with her legs crossed. I was infatuated with her. . . . (Ernie Tallarico)

As soon as I was old enough, they put me to work. First it was clipping hedges. When I snapped back, “What do I have to do that for?” my uncle said, “Just make it nice and shut up.” He used to call me Skeezix. He’d spent most of World War II in the Fiji Islands, so he knew how to take care of business and anything else that gave us any trouble. I helped him dig ditches and put in a water pipeline over a mile of mountain and dug a pond with my bare hands. I washed pots and dishes at night and mowed the lawns with my father when I was old enough to push a mower. I cleaned toilets, made the beds, and picked up all the cigarette butts that the guests left behind.

We would rake up the hay with pitchforks and put it in the barn below the lower forty. The downstairs of the barn was empty except for maple syrup buckets and wooden and metal taps for the trees that some family had left before we lived there. It was quite an adventure going down there—full of spiderwebs, stacks of buckets, glass jars, and artifacts from the twenties and thirties—all those dusty, rusty things kids love to get into—me in particular.

Upstairs in the barn, there was a hayloft door with an opening where you’d load the hay in and out. I could climb up there and jump down from the rafters of the ceiling. I did my first backflip in that barn, because the hay was so soft, it was like landing on, well, hay. I always kept an eye out for pitchforks left behind. Land on one of those suckers and I would have learned how to scream the way I do now . . . twenty years earlier.

Before I could go to the beach with the rest of the guests I had to finish doing my chores. After a while I came up with a plan. It was called: get up earlier.

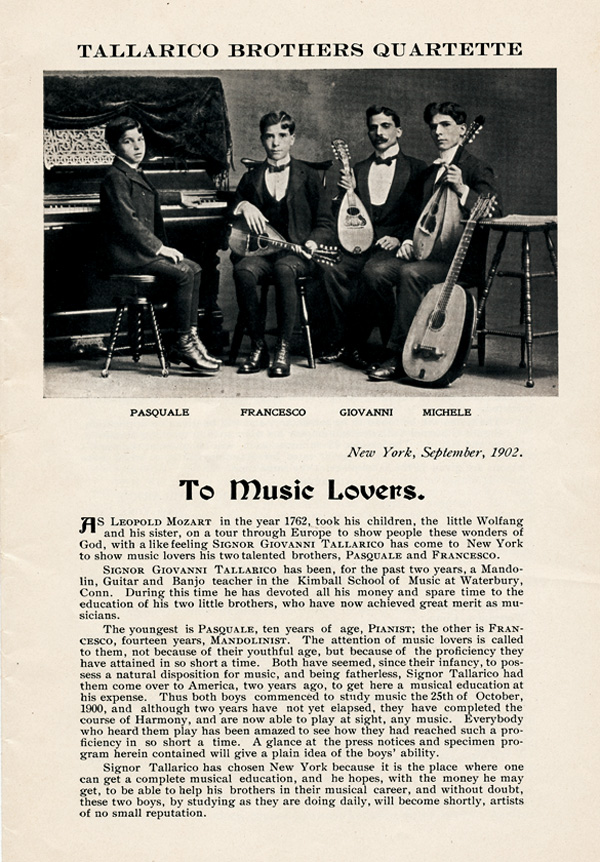

Every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday during the summer my father played the piano at Soo Nipi Lodge along with my uncle Ernie on sax. They had a trumpet player named Charlie Gauss, a stand-up bass player named Stuffy Gregory, and a drummer who will go unnamed. Soo Nipi Lodge—which today would probably be called Snoop Dog Lodge—was one of the classic old hotels, like the one in The Shining: all wooden and splendiferous and huge, with dining rooms and decks outside with rocking chairs and screened-in porches. Chill central by today’s standards. They began building these resorts in the 1870s, when horses and buggies brought the guests from the train station to the hotels. The only thing missing was the musicians to play music and entertain the guests—and this is probably how the Tallarico brothers came to buy the land there.

During Prohibition, people would take the train up from New York to Sunapee, and the booze would come down from Canada. Some folks drank, some didn’t. Maybe they came up for the weekend to see the leaves turn, but I have a funny feeling they got on the train for a quick weekend away—take horse-and-buggy rides, stay at the big hotels, and cruise in the old steamboats. The ones in Sunapee Harbor today are replicas of the original ones from a hundred years ago. Very quaint. Ten miles up the road was New London, the original Peyton Place, where, oddly enough, Tom Hamilton was born. But then again, it all makes perfect sense to me now.

On Sunday nights, Dad would give recitals at Trow-Rico. People from miles around would come over to hear him, and my grandma, my mother, and my sister would play duets. All the families that came up had kids, and Aunt Phyllis would holler, “C’mon, Steven, let’s put on a show for them!” Downstairs from the piano room was the barn’s playroom: Ping-Pong, a jukebox, a bar, and, of course, a dartboard. There was also a big curtain across one corner of the room that made a stage where my aunt Phyllis taught all the kids camp songs like “John Jacob Jingleheimer Schmidt” and the “Hole in the Bucket” song. I would pantomime to an old 78 recording of “Animal Crackers.” It was an evening of camp-style vaudeville. For the finale, we hung a white sheet in front of a table made from two sawhorses and a board. Someone from the audience would be brought back to lie on the board, and behind them a giant lamp cast shadows on the sheet. My uncle Ernie would perform an operation on the person lying down, pretending to saw him in half and eventually pull out a baby—quite horrifying and hilarious to the audience. It was all very tongue-in-cheek but certainly the beginning of my career.

We must have done a hundred and fifty or more of those shows over the years. I was a serious ham. I’d do cute things kids can get away with—especially to adoring relatives. It was like something from a Mickey Rooney movie. I’d learned all the lyrics to that song “Kemo-Kimo.”

Keemo kyemo stare o stare

Ma hye, ma ho, ma rumo sticka pumpanickle

Soup bang, nip cat, polly mitcha cameo

I love you

And then I’d add something like “Sticky sticky Stambo no so Rambo, had a bit a basket, tama ranna nu-no.” What the hell was that? The beginning of my love for real out-there music and crazy lyrics.

Before I got involved in doing chores at Trow-Rico, before I discovered girls and pot and playing in bands, I had a great life in the woods with my slingshot and BB gun. As soon as we got up there, I’d be gone in the woods and fields. And I never came back till dinnertime. I was a mountain boy, barefoot and wild. I walked through the woods, looked up at the trees, the birds, the squirrels—it was my own private paradise. I’d tie a stick to a rope and make a swing from any tree branch. I was brought up that way, a wild child of the woods and ponds. But of course, nobody believes that about me. They don’t know what to think when I say, “You know, I’m just a country boy.”

1961—we all gotta start somewhere. . . . (Ernie Tallarico)

No waves, no wind. If you go into a recording studio that’s soundproofed, something just feels wrong to your ears. Especially when they close the door—that’s sound deprivation, it’s anechoic, without echo, without sound. Not so in the woods. In that silence I heard something else there, too.

I lost all that mystery when I was on drugs. Coming out of that din I was able to feel my spiritual connection to the woods again. Drugs will steal you like a crook. Spirituality, over. I could no longer see the things I used to see in my peripheral vision. No periphery, no visions.

I used to go up in the woods and sit by myself and hear the wind blow. As a kid, I’d come across places where the woodland creatures lived. Tiny human creatures. I’d see mossy beds, cushions of pine needle, nooks and crannies under the roots of upturned trees, hollow logs. I’d look around for elves, because how could it be that beautiful and strange and nobody live there! All of this tweaked my imagination into such a state that I knew there was something there besides me. If you could sleep on moss that thick it would be bliss. I’d smell that green grass. I would see a natural little grotto in the woods and say to myself, “That’s where their house must be.”

A few years ago I found a moss bed for sale at this lady’s little store in New London. The place was full of nature stuff—and had a big wooden arch in front and giant bird wings. The bed is made of twigs, with a moss mattress, grouse feathers for pillows, a wooden nest, an ostrich egg cracked in half with a little message on it, and the prints of the fairies that were born on the bed. We kept it in the house so my two children, Chelsea and Taj, would see it and just know that fairies were born on that bed. They’d say, “For real?” and I’d say, “For real.”

I bought the two fields I used to go walking in. I haven’t gone out into the woods lately to see if they’ve been touched; I’m afraid to find out if it’s all still there as I remember it. But I grew up with these creatures. I was alone in the forest but I was never lonely. That’s where my first experiences of otherness came from, of the other world. My spiritual ideas didn’t come from the Lord’s Prayer or church or pictures in the Bible, they came from the stillness. The silence was so different from anything I would ever experience. The only noise that you heard in a pine tree forest was the gentle whistling sound of the wind blowing through the needles. Other than that, it’s just quiet . . . like after a fresh snow. . . . It really quiets down in the woods . . . cracking branches . . . nothing. It’s like when I took acid—I felt the wind brushing against my face although I knew I was in the bathroom and the door was closed. This was Mother Nature talking to me.

I would walk through the woods and walk and walk. I would find chestnut trees, fairy rings of mushrooms, bird’s nests made with human hair and fishing line. I would imagine I was in the jungle in Africa and climb up on the gates at the entrances to the big estates and sit on the stone lions (until someone shouted, “Get down from there, kid!”).

That’s where my spirit was born. Of course I got introduced to spirituality through religion, too, from the Presbyterian Church in the Bronx and my choir teacher, Miss Ruth Lonshey. At the age of six, I learned all the hymns (and a few hers). I fell in love with two girls on either side of me in the choir. And of course they had to be twins. I remember being five and sitting next to my mother in a pew at that church, looking up at the altar that held the Bible and a beautiful golden chalice, with the minister looming over it. There was a golden tapestry that hung down to the floor with a crucifix embroidered on the front. I was all wrapped up in the tradition of getting up, sitting down, getting up, singing, sitting down, praying, singing, praying, getting up, praying, singing, and hoping all this would take me somewhere closer to heaven. I thought for sure God must be RIGHT THERE under THAT altar. Just as I’d thrown a blanket over the dining room chairs to create a fortress, a safe, powerful place, kinda churchlike, with the added bonus of imagination. WOW, all of this combined together in one beautiful moment of ME, feeling GOD. But then I’d met Her once before in the forest.

I would walk in Sunapee with a slingshot in my back pocket over the meadow and through the woods until I got lost . . . and that’s when my adventure would begin. I would come upon giant trees so full of chestnuts that the branches would bend, bushes full of wild blackberries, raspberries, and chokecherries, acres of open fields full of wild strawberries in the grass—so much so that when I was mowing the lawn, it smelled like my mom’s homemade jam. I would find animal footprints, hawk feathers, fireflies, and mushrooms in the shape of Hobbit houses that I was told were left by Frodo and Arwin from Lord of the Rings. Incidentally, those were the same mushrooms that I would later eat and that would magically force my pen to write the lyrics to songs like “Sweet Emotion.” In choir, I was singing to God, but on mushrooms, God was singing to me.

I pretended I was a Lakota Indian with a bow and arrow—“One shot, one kill”—only I had my BB gun—“One BB, one bird.” Me and my imaginary buddy Chingachogook, moving silently through the woods. I was a deadeye shot; I’d come back after an afternoon of killing with my slingshot and Red Ryder BB gun with a string of blue jays tied to my belt. That part wasn’t imaginary. I had watched every spring how blue jays raided the nests of other birds and flew away with their babies. My uncle had told me that blue jays were carnivorous, just like hawks and lawyers.

I’d go out fishing with my dad on Lake Sunapee in a fourteen-foot, made-in-the-forties, very antique, giant wooden 270-pound rowboat that only a Viking could lift. The handles on the oars alone were thicker than Shaq at a urinal. You’re out in the center of the lake, sun beating down like in the Sahara. You’re burning, you can’t go any farther. By the time we rowed out to the middle, where the BIG ONES were biting, we all realized we had to row back. We being ME. A-ha-ha-ha! I became Popeye Tallarico. Mowing the lower forty acres once a week gave me the shoulders to row back to shore (and to carry the weight of the world).

Up in the woods from the lake there were great granite boulders pushed there by glaciers during the Ice Age. There were caves up above the road I lived on in Sunapee with Indian markings on the walls—pictographs and signs. They were discovered when the town was settled back in the 1850s. The Pennacook Indians lived in those very caves. After killing off all the Indians, the whites built and named a seventy-five-room grand hotel after them, Indian Cave Lodge, the first of three grand hotels in the Sunapee area and the first place where I played drums with my dad’s band back in 1964—also just a half a mile away from where I first saw Brad Whitford play.

In the town of Sunapee Harbor there used to be a roller-skating rink. It had been an old barn; they opened up the door on the right side and the door on the left side and they poured cement around the outside of the barn so you could skate around the barn and through the middle out the other side. As a kid, it was a great little roller-skating rink. And back then, you could rent skates on the inside of the barn along the back wall and buy a soda pop, which they would put in cups that you could grab as you skated on by. Later on they put a little stage where a band could play behind where they rented the skates. By the next summer, not only could you roller-skate, but you could also rock ’n’ roller-skate to your favorite band. It was the first of its kind and it was called the Barn. Across the street was a restaurant called the Anchorage. You could pull your boat up and after a long day of waterskiing, sunbathing, or fishing-with-no-luck, get fish and chips. . . . And speaking of chips, no one made french fries better than one of the cooks that worked at the Anchorage—Joe fucking Perry. I went back there to shake his hand and there he stood in all his glory, horn-rimmed black glasses with white tape in the middle holding them together. He looked like Buddy Holly in an apron. I said, “Hi, how are ya?” or was it, “How high are ya?” At the time I was with a band called The Chain Reaction—and little did I know that my future lay somewhere between the french fries and the tape that held his glasses together.

At the end of each summer I’d go back to the Bronx, which was a 180-degree culture shock. A return to the total city—tenements, sidewalks—from total country—where the deer and the antelope rock ’n’ roam. Haven’t met many people who experienced that degree of transition. Where we lived was the equivalent of the projects: sirens, horns, garbage trucks, concrete jungle—versus the country—rotted-out Old Town canoe bottoms from the early 1900s, remnants from the last generation who once knew the original Indians. Holy shift! By September 1, all the tourists who made New Hampshire quiver and quake for a summer of fun had fled for the city from whence they came like migrating birds. Welcome to the season of wither. One was grass, green, and good old Mother Nature, and the other was cement sidewalks, subways, and switchblades. But somehow I still found a way to be a country boy, so even in the city I could be Mother Nature’s son—but with attitude.

Kids would ask me, “Where’d you go?” I’d tell them, “Sunapee!” Sunapee was a great mysterious Indian name. It was like coming from a different planet. When I got back to the city I would invent fantastic adventures for myself: escaping from a grizzly bear, attacked by Indians. “You’ve got a .22?” “You what?” And then I started the bullshit: “I got bit by a rattlesnake . . . ,” showing them a scar I got falling into the fireplace that summer. It was kind of like believing your own lie; you tell a lie and it grows. “The thing came at me, it was drooling, it had blood on its fangs from the camper it’d recently killed.” “You’re kidding me?” “No, seriously, it was rabid, but I nailed it right between the eyes with my .22.” Well, I didn’t want to say I was mowing lawns and taking garbage to the dump. That didn’t cut it with the girls, or the guys who wanted to beat you up if you didn’t represent a Bronx-type attitude. I wanted to talk about how I killed a grizzly with my bare hands—I was Huck Finn from Hell’s Kitchen. City people have bizarre ideas about the country anyway, so I could make up anything I liked and they’d believe me. Remember, this was 1956. And Ward Cleaver actually had a son, not a wife, named . . . Beaver.

I was about nine when we moved from the Bronx to Yonkers. I hated being called Steve. I was known as Little Stevie to my family and that’s cool because that’s my family. But being called Steve by anyone other than my family sucked. Getting moved from the Bronx to a place called Yonkers (a name almost as bad as Steve) took a little adjusting to. It was too white and Republican for a skinny-ass punk from the Bronx. My best friend’s name was Ignacio and he told me to use my middle name, which is Victor, a-lika my poppa! This suggestion, coming from a kid whose name sounds like an Italian sausage, was perfect. So for a year everyone called me Victor and that’s just how long that lasted.

At twelve, my first band . . . me, Ignacio, and Dennis Dunn. (Ernie Tallarico)

Moving from the Bronx to Yonkers was okay because we lived in a private house with a huge backyard and woods everywhere. There was a lake used as a reservoir two blocks from my house, where my friends and I fished our teenage years off. It was filled with frogs, salmon, perch, and every other kind of fish. There were skunks, snakes, rabbits, and deer in my backyard. There was so much wildlife in those woods that we all started trapping animals, skinning them, and selling their fur for pocket money, a kind of backwoods hobby I learned from the 4-H friends I grew up with in New Hampshire. When I was fifteen I found a toy store that sold wading pools for toddlers in the shape of a boat. I bought one and humped it down to the lake, paddled out and picked up all the lures that were caught in the weeds. I wound up selling them to the same people who had lost them to begin with. I was a reservoir dog before it was a movie.

At fourteen I found this pamphlet in the back of Boy’s Life or some other wildlife magazine, with an ad for Thompson’s Wild Animal Farm in Florida. You could buy anything from a panther to a cobra to a tarantula to a raccoon. A baby raccoon? Wow, I gotta have one! I sent away and it arrived in a wooden crate looking up at me with eyes like a Keane painting or a Japanese anime schoolgirl. I gave him a bath, threw him over my shoulder, and headed down to the lake. It was there that he taught me how to fish all over again. I named him Bandit because when you turned your back he would either pick your pockets or steal all the food out of the refrigerator. After a year of his ripping the house apart, I realized that a wild animal kept in the house is not the same as having a domestic animal as a pet, so I had to keep him in the backyard. You’ve got to just feed them and let them be wild. If you take them in, they adopt your personality—and at age sixteen, I was full of piss ’n’ vinegar, which is not what you want a wild animal to be. He ripped down every curtain my mom put up in the house. I loved Bandit and he changed my mind about killing animals. I wound up giving him away to a farmer in Maine where he grew to a ripe old age, huge and fat. Eventually chewing his way to freedom, he bit through an electric wire and burned down the barn. You can still see his face in Maine’s Most Wanted. Way to go, Bandit!

Back in the Bronx, the kids would assemble in the courtyard every morning at good ’ol P.S. 81. “All right, class, line up!” at 8:15 A.M. sharp. One morning when I was in third grade, there was a girl in the courtyard and I must have grabbed a broken lightbulb and chased her around—like any smart (ass) little boy looking for affection would do. This was my way of proving that there was more to adolescent courtship than snakes and snails and puppy dog tails.

Her mother went to the principal’s office. “If Steven Tallarico’s not thrown out of this school, I’m taking my daughter out! He chased my daughter with a LETHAL WEAPON (blah blah blah). He’s an animal!” I was already Peck’s Bad Boy, and this didn’t help. They brought my mom in. They wanted to send me to a school for wayward lads and lassies, who are known today as ADHD kids.

“What? Are you kidding?” my mother said to the principal. My mom was soooo for me. “You know what? I’m takin’ him out of this school. Fuck you!” She didn’t say that, but her EYES did. And she DID take me out. I moved on to the Hoffmann School, which was a private school in Riverdale hidden in the woods, oddly enough, by Carly Simon’s house. Unbeknownst to me, Carly also lived nearby in Riverdale. Thirty years later, when we did a concert toether on Martha’s Vineyard, she told me that she also went to the Hoffmann School.

I was excited about the Hoffmann School, but I get to the place and find out it’s full of “spaycial kids.” Kids that go “Fuck YOU!” in the middle of class, who have some Tourette-type syndrome and scream their lungs out. A little wilder than public school, I would say: kids sniffing the glue during art class and writing graffiti in the hallways . . . kids eating finger paint and everyone shooting spitballs with rubber bands at each other. WOW, my kind of place!

These were kids like me, hyper, acting-out kids—real brats! Not that I was that exactly. I just had too much Italian in me, the kind of Italian who, you know, is loud, opinionated, in-your-face, with no brakes. But I knew that if I totally let go, there was going to be fucking cause and effect and it would end with a ruler across my knuckles. Still, I’d do anything I could think of. I remember once combing my hair in the lunchroom with a fork! That time I got off easy; setting a fire in a trash can was a different story.

So that was the Bronx, still somewhat wild. On my way to the Hoffmann School I cut through a field, jumping over a stone wall. Over the river and through the woods. There was a cherry tree that was so thick and fat, the size of an elm tree, and when it bloomed it was like an explosion of pink and white petals, like a snowstorm. In summer it was loaded with cherries.

I’d go around behind the apartment buildings looking for stuff to get into. I found this big, beautiful pile of dirt, which later I realized was landfill from all the apartment buildings in that area. A ten-story mountain of dirt you had to climb as if you were scaling Mount Everest. A kid’s dream! To me that pile of dirt was a mountain—Mount Tallarico. “Let’s go climb the mountain,” I’d tell my friends. When you got to the top of it there was a whole acre of land with weeds and saplings—and praying mantis nests and all sorts of things that no one could get to. Of course I had to bring a praying mantis nest home. It looked like something from between my legs—all round, tight, wrinkly, and kinda figlike. I hid it in my top drawer because I thought it was so cool. I woke up two weeks later and my room was full of little baby praying mantises—thousands of them! They’d just infested the place, all over our bunk beds, blankets, pillows, on the walls, and . . . “Mom!”