Полная версия

A Prince of Troy

A PRINCE OF TROY

Lindsay Clarke

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain as part of The War at Troy by HarperCollinsPublishers 2004

Copyright © Lindsay Clarke 2004

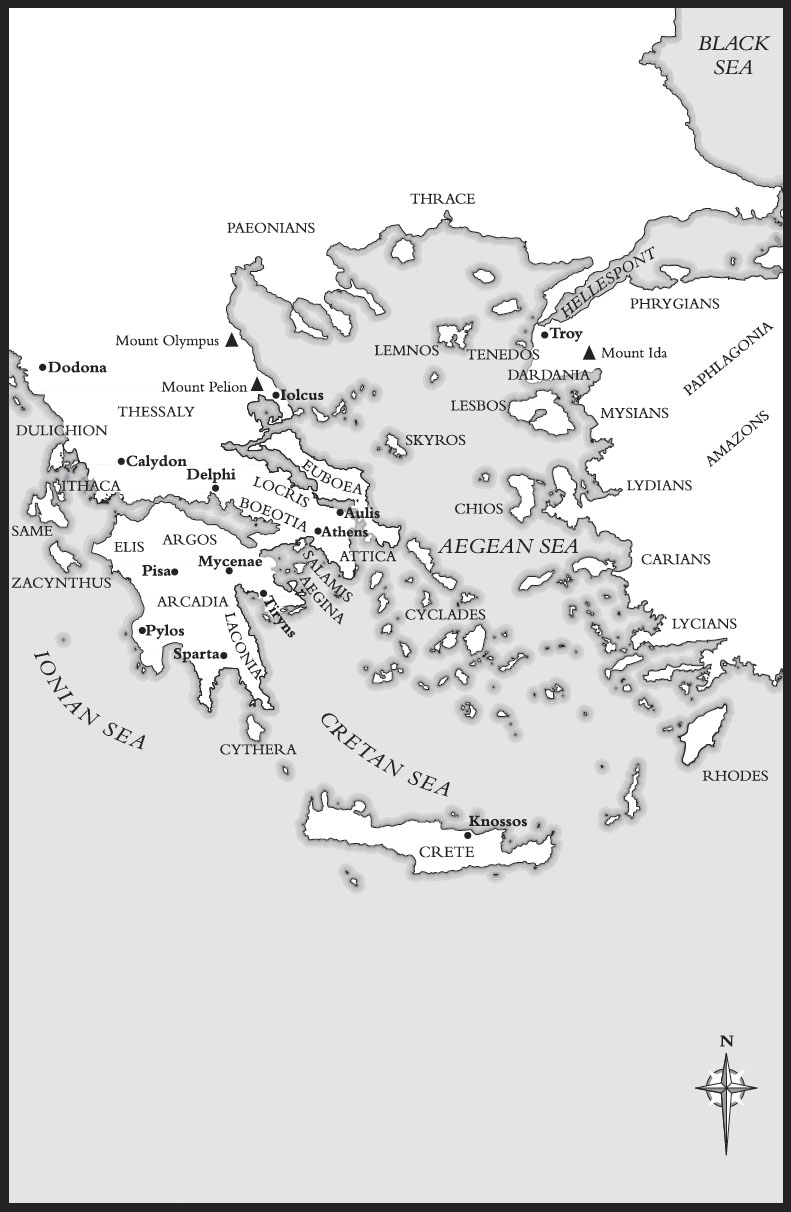

Map © Hardlines Ltd.

Cover illustrations © Shutterstock.com

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Lindsay Clarke asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008371043

Ebook Edition © September 2019 ISBN: 9780008371036

Version: 2019-09-30

Dedication

For

Sean, Steve, Allen and Charlie

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

The Bard of Ithaca

The Apple of Discord

An Oracle of Fire

The Judgement of Paris

Priam’s Son

A Horse for Poseidon

The Supplicant

The Trojan Embassy

The Madness of Aphrodite

The Flight from Sparta

A Perfect Case for War

Glossary of characters

Acknowledgements

Also by Lindsay Clarke

About the Publisher

Map

The Bard of Ithaca

In those days the realm of the gods lay closer to the world of men, and the gods were often seen to appear among us, sometimes manifesting as themselves, sometimes in human form, and sometimes in the form of animals. Also the people who lived at that time were closer to gods than we are and great deeds and marvels were much commoner then, which is why their stories are nobler and richer than our own. So that those stories should not pass from the earth, I have decided to set down all I have been told of the war at Troy – of the way it began, of the way it was fought, and of the way in which it was ended.

Today is a good day to begin. The sun stands at its zenith in the summer sky. When I lift my head I can hear the sound of lyres above the sea-swell, and voices singing in the town, and the beat of feet stamping in the dance. It is the feast day of Apollo. Forty years ago today, Odysseus returned to Ithaca, and I have good reason to recall that day for it was almost my last.

I was twenty years old, and all around me was blood and slaughter and the frenzy of a vengeful man. I can still see myself cowering beside the silver-studded throne. I remember the rank taste of fear in my mouth, the smell of blood in my nose, and when I close my eyes I see Odysseus standing over me, lifting his bloody sword.

Because Ares is not a god I serve, that feast of Apollo was the closest I have come – that I ever wish to come – to war. Yet the stories I have to tell are the tales of a war, and it was from Odysseus that I had them. How can that be? Because his son Telemachus saved me from the blind fury of Odysseus’s sword by crying out that I was not among those who had sought to seize his wife and kingdom. So I was there, later, beside the hearth in the great hall of Ithaca, long after the frenzy had passed, when Odysseus told these stories to his son.

One day perhaps some other bard will do for Odysseus what I, Phemius of Ithaca, have failed to do and make a great song out of these stories, a song that men will sing for ever. Until that day, may a kind fate let what I set down stand as an honest man’s memorial to the passions of both gods and men.

The Apple of Discord

The world is full of gods and no one can serve all of them. It is true, therefore, that a man’s fate will hang upon the choices that he makes among the gods, and most accounts now say that the war at Troy began with such a choice when the Trojan hero Paris was summoned before the goddesses one hot afternoon on the high slopes of Mount Ida.

The Idaean Mountains stand some ten miles from the sea, across the River Scamander in that part of the kingdom of Troy which is known as Dardania. Odysseus assured me that an ancient cult of Phrygian Aphrodite existed among the Dardanian clan of Trojans at that time, and that as one of their chief herdsmen, Paris would have grown up in an atmosphere charged with the power of that seductive goddess. So it seems probable that he was gifted with a vision that brought him into her divine presence during the course of an initiatory ordeal on the summit of Mount Ida. But it is not permissible to speak directly of such secret rites, so we bards must employ imagination.

It began with a prickling sensation that he was being watched. Paris looked up from a pensive daydream and saw only his herd of grazing animals. They seemed, if anything, less alert than he was. Then, out of the corner of his eye, he caught a brief shimmering of light. When he turned his head, the trembling in the air shifted to the other side. Perplexed, Paris moved his gaze in that direction and heard a soft chuckle. Directly ahead of him in the dense shade of a pine, a male figure shivered into focus. Wearing a broad-brimmed travelling-hat and a light cloak draped across his slender form, he leaned against the trunk of the tree with the thumb of one hand tucked into his belt and holding a white-ribboned wand in the other. His head was tilted quizzically as though to appraise the herdsman’s startled face.

Paris leapt to his feet, sensing that he was in the presence of a god.

A buzzard still glided through the sky’s unsullied blue. The familiar view stretched below him to the rivers watering the plain of Troy. Yet it was as though he had stepped across a threshold of light into a more intense arena of awareness, for the feel of everything was altered. Even the air tasted thinner and sharper as though he had been lifted to a higher altitude. And it was the god Hermes who gestured with his staff.

‘Zeus has commanded me to come. We need to talk, you and I.’

And with no sign of having moved at all, he was standing beside Paris, suggesting that they both recline on the grass while he explained his mission.

‘Firstly,’ Hermes said, ‘you might care to examine this.’ He took something shiny from the bag slung at his belt and handed it to Paris who looked down at the flash of sunlight from the golden apple that now lay in the palm of his hand. Turning it there, he ran his thumb over the words of an inscription and glanced back up at the god in bewilderment.

Hermes smiled. ‘It says To the Fairest. Pretty, isn’t it? But you wouldn’t believe the trouble it’s caused. That’s what brings me here. We gods are in need of help, you see.’ He took in the young man’s puzzled frown. ‘But none of this will make any sense to you unless I first tell you something of the story of Peleus.’

It’s possible, I suppose, that it all started that way, though Odysseus always insisted that the war at Troy began where all wars begin – in the hearts and minds of mortal men. By then he had come to think of war as a dreadful patrimony passed on from one generation to the next, and he traced the seeds of the conflict back to the fathers of the men who fought those battles on the windy plain. Peleus was one of those fathers.

Odysseus himself was still a young man when he befriended Peleus, who had long been honoured as among the noblest souls in a generation of great Argive heroes. There had been a time too when Peleus had seemed, of all mortals, the one most favoured by the gods. Yet, much to his dismay, the young Ithacan adventurer found him to be a man of sorrows, prone to long fits of silent gloom over a life that had been shadowed by terrible losses. During the course of a single night Peleus told Odysseus as much of his story as he could bear to tell.

It began with a quarrel among three young men on the island of Aegina, a quarrel which ended with two of them in exile, and the other dead. Only just out of boyhood, Peleus and Telamon were the elder sons of Aeacus, a king renowned throughout all Argos and beyond for his great piety and justice. If Aeacus had a weakness it was that he favoured the youngest of his sons, a youth named Phocus, who had been born not to his wife, but to a priestess of the seal-cult on the island.

Displaced in their ageing father’s affections, Peleus and Telamon nursed a lively dislike for this good-looking half-brother who was as sleek and muscular as the seal for which he was named, and excelled in all things, especially as an athlete. Their resentment turned to hatred when they began to suspect that Aeacus intended to name Phocus as his successor to the throne. Why else should he have been recalled to the island after he had voluntarily gone abroad to keep the peace? Certainly, the king’s wife thought so, and she urged her own sons to look to their interests.

What happened next remains uncertain. We know that Telamon and Peleus challenged their half-brother to a fivefold contest of athletics. We know that they emerged alive from that contest and that Phocus did not. We know too that the elder brothers claimed that his death was an accident – a stroke of ill luck when the stone discus thrown by Telamon went astray and struck him in the head. But there were also reports that there was more than one wound on the body, which was, in any case, found hidden in a wood.

Aeacus had no doubt of his sons’ guilt, and both would have been killed if they had not realized their danger in time and fled the island. But the brothers then went separate ways, which leads me to believe that Peleus spoke the truth when he told his friend Odysseus that he had only reluctantly gone along with Telamon’s plan to murder Phocus.

Whatever the case, when his father refused to listen to his claims of innocence, Telamon sought refuge on the island of Salamis, where he married the king’s daughter and eventually succeeded to the throne. Peleus meanwhile fled northwards into Thessaly and found sanctuary there at the court of Actor, King of the Myrmidons.

Peleus was warmly welcomed by King Actor’s son Eurytion. The two men quickly became friends, and when he learned what had happened on Aegina, Eurytion agreed to purify Peleus of the guilt of Phocus’s death. Their friendship was sealed when Peleus was married to Eurytion’s sister Polymela.

Not long after the wedding, reports came in of a great boar that was ravaging the cattle and crops of the neighbouring kingdom of Calydon. When Peleus heard that many of the greatest heroes of the age, including Theseus and Jason, were gathering to hunt down the boar, and that his brother Telamon would be numbered among them, he set out with Eurytion to join the chase.

Outside of warfare, there can rarely have been a more disastrous expedition than the hunt for the Calydonian boar. Because the king of that country had neglected to observe her rites, Divine Artemis had driven the boar mad, and it fought for its life with a fearful frenzy. By the time it was flushed into the open out of a densely thicketed stream, two men had already been killed, and a third hamstrung. An arrow was loosed by the virgin huntress Atalanta which struck the boar behind the ear. Telamon leapt forward with his boar-spear to finish the brute off, but he tripped on a tree-root and lost his footing. When Peleus rushed in to pull his brother to his feet, he looked up and saw the boar goring the guts out of another huntsman with its tusks. In too much haste, he hurled his javelin and saw it fly wide to lodge in the ribs of his friend Eurytion.

With two deaths on his conscience now, Peleus could not bear to face his bride Polymela or his friend’s grieving father. So he retreated to the city of Iolcus with one of the other huntsmen, King Acastus, who offered to purify him of this new blood-guilt. But the shadows were still deepening around Peleus’s life for while he was in Iolcus, Cretheis, the wife of Acastus, developed an unholy passion for him.

Embarrassed by her approaches, Peleus tried to fend her off, but when he rebuffed her more firmly, she sulked at first, and then her passion turned cruel. To avenge her humiliation, she sent word to Polymela that Peleus had forsaken her and intended to marry her own daughter. Two days later, having no idea what Cretheis had done, and assuming therefore that all the dreadful guilt of it was his, Peleus learned that his wife had hanged herself.

For a time he was out of his mind with grief. But his trials were not yet over. Alarmed by the consequences of her malice, Cretheis sought to cover her tracks by telling her husband that Peleus had tried to rape her. But having bound himself to Peleus in the rites of cleansing, Acastus had no wish to incur a sacrilegious blood-guilt of his own, so he took advice from his priests. Some time later he approached Peleus with a proposal.

‘If you dwell on Polymela’s death too long,’ he said, ‘you’ll go mad from grief. Eurytion’s death was an accident. In the confusion of the chase, it could have happened to anyone. And if your wife couldn’t live with the thought of it, you are not to blame. You must live your life, Peleus. You need air and light. How would it be if you and I took to the mountains again? If I challenged you to a hunting contest would you have the heart to rise to it?’

Thinking only that his friend meant well by him, Peleus seized the chance to get away from the pain of his blighted life. A hunting party was assembled. Taking spears and nets, and a belling pack of dogs, Peleus and Acastus set out at dawn for the high, forested crags of Mount Pelion. They hunted all day and at night they feasted under the stars. Relieved to be out there at altitude, in the uncomplicated world of male comradeship, Peleus drank too much of the heady wine they had brought, and fell into a stupor of bad dreams.

He woke in the damp chill of the early hours to find himself abandoned beside a burned-out fire, disarmed, and surrounded by a shaggy band of Centaur tribesmen who stank like their ponies and were arguing in their thick mountain speech over what to do with him. Some were for killing him there and then, but their leader – a young buck dressed in deerskins, with a bristling mane of chestnut hair – argued that there might be something to be learned from a man who had been cast out by the people of the city, and they decided to take him before their king. So Peleus was kicked to his feet and hustled upwards among steep falls of rock and scree, through gorse thickets and stands of oak and birch, across swiftly plunging cataracts, and on into a high gorge of the mountain that rang loud with falling water.

As the band approached with their prisoner, a group of women looked up from where they were beating skins against the flat stones of a stream and fell silent. The leader of the band climbed up a stairway of rocks and entered a cave half-way up a cliff-face. Kept waiting below, Peleus took in the stocky, untethered ponies that grazed a rough slope of grass. Goats stared at him from the rocks through black slotted eyes. He could see no sign of dwellings but patches of charred grass ringed with stones showed where fires were lit, and his nose was assailed by a pervasive smell of raw meat and rancid milk. Two children clad in goatskin smickets came to stand a few yards away. Their faces were stained with berry-juice. If he had moved suddenly, they would have shied like foals.

Eventually he was brought inside the cave where an old man with lank white hair, and shoulders gnarled and dark as olive wood, reclined on a pallet of leaves and deeply piled fresh grass. The air of the cave was made fragrant by the many bundles of medicinal herbs and simples hanging from its dry walls. The man gestured for Peleus to sit down beside him and silently offered him water from an earthenware jug. Then, wrinkling his eyes in a patient smile that seemed drawn from what felt like unfathomable depths of sadness, he spoke in the perfect, courtly accent of the Argive people. ‘Tell me your story.’

Peleus later told Odysseus that he regained his sanity in his time among the Centaurs, but the truth is that he was lucky to fall into their hands at a moment when their king, Cheiron, was gravely concerned for the survival of his tribe.

The Centaurs had always been a reclusive, aboriginal people, living their own rough mountain life remote from the city dwellers and the farmers of the plain. Cheiron himself was renowned for his wisdom and healing powers and had, for many years, run a wilderness school in the mountains to which many kings used to send their sons for initiation at an early age. Pirithous, King of the Lapith people on the coast, had attended that school when he was a boy and always cherished fond memories of King Cheiron and his half-wild Centaurs. For that reason he invited them to come as guests to his wedding feast, but that day someone made the mistake of giving them wine to drink. The wine, to which their heads were quite unused, quickly maddened them. When they began to molest the women at the feast, a bloody fight broke out in which many people were killed and injured. Since that terrible day the tribe of Centaurs had been regarded by the uninitiated as less than human. Those who survived the battle at the feast fled to the mountains where men hunted them down like animals for sport.

By the time Peleus was brought before Cheiron in his cave there were very few of his people left. So during the long hours when they first talked, the two men came to recognize each other as noble souls who had suffered unjustly. At that moment Peleus had no desire to return to the world, so he accepted the offer gladly when Cheiron suggested that he might heal his wounded mind by living a simple life among the Centaurs for a time.

The days of that life proved strenuous, and in the nights Peleus was visited by vivid, disturbing dreams which Cheiron taught him how to read. He felt healed too by the music of the Centaurs, which seemed filled with the strains of wind and wild water yet had a haunting enchantment of its own. Through initiation into Cheiron’s mysteries, Peleus rediscovered meaning in his world. And through his bond with Peleus, Cheiron began to hope that one day he might ensure the survival of his tribe by restoring good relations with the people of the cities below. So as well as friendship, the old man and the young man found hope in one another. That hope was strengthened one day when Peleus said that if he ever had a son, he would certainly send him to Cheiron for his education, and would encourage other princes to do the same.

‘But first you must have a wife,’ said Cheiron, and when he saw Pelion’s face darken at the memory of Polymela, the old man stretched out a mottled hand. ‘That dark time is past,’ he said quietly, ‘and a new life is opening for you. Several nights ago Sky-Father Zeus came to me in a dream and told me that it was time for my daughter to take a husband.’

Amazed to discover that Cheiron had a daughter, Peleus asked which one of the women of the tribe she might be. ‘Thetis has not lived among us for a long time,’ Cheiron answered. ‘She followed her mother’s ways and became a priestess of the cuttlefish cult among the shore people, who honour her as an immortal goddess. She has given herself as daughter to the sea-god Nereus, but Zeus wants her and her cult must accept him. She is a woman of great beauty – though she has sworn never to marry unless she marries a god. In my dream, however, Zeus said that any son born to Thetis would prove to be even more powerful than his father, so she must be given to a mortal man.’ Cheiron smiled. ‘That man is you, my friend – though you must win her first. And to do that, you must undergo her rites and enter into her mystery.’

As with all mysteries, the true nature of the shore women’s rites can be comprehended only by those who undergo them, so I can tell only what Odysseus told me of the account Peleus gave him of his first encounter with Thetis. It took place on a small island off the coast of Thessaly. Cheiron had advised him that his daughter was often carried across the strait on a dolphin’s back. If Peleus concealed himself among the rocks, Thetis might be caught sleeping at mid-day in a sea-cave on the strand.

Following his mentor’s instructions, Peleus crossed to the island, took cover behind a myrtle bush, and waited till the sun rose to its zenith. Then all his senses were ravished as he watched Thetis gliding towards the shore in the rainbow spume of spindrift blowing off the back of the dolphin she rode. Naked and glistening in the salt-light, she dismounted in the surf and waded ashore. He followed her at a distance, keeping out of sight, till she entered the narrow mouth of a sea-cave to shelter from the noonday sun.

Once sure she was asleep, he made his prayer to Zeus, lay down over her and clasped her body in a firm embrace. Thetis started awake at his touch, alarmed to find her limbs pinioned in the grip of a man. Immediately her body burst into flame. A torrent of fire licked round Peleus’s arms, scorching his flesh and threatening to set his hair alight, but Cheiron had warned him that the nymph had acquired her sea-father’s power of shape-shifting, and that he must not loosen his hold for a moment whatever dangerous form she took. So he grasped the figure of flame more tightly as Thetis writhed beneath him and took him on a fierce dance that wrestled him through all the elements.

When she saw that fire had failed to throw him, the nymph again changed shape. Peleus found himself floundering breathlessly as he clutched at the weight of water in a falling wave. His ears and lungs felt as though they were about to burst, but still he held on until the waters vanished and the hot maw of a ferocious lion was snarling up at him, only to be displaced in turn by a fanged serpent that hissed and twisted round him, viciously resisting his embrace. Then, under his exhausted gaze, the serpent took the shape of a giant cuttlefish, which sprayed a sticky gush of sepia ink over his face and body. Already burnt, half-drowned, mauled by fangs and talons, and almost blinded by the ink, Peleus was on the point of releasing his prize, when Thetis suddenly yielded to this resolute mortal who had withstood all her powers.

Gasping and breathless, Peleus looked down, saw the nymph resume her own beautiful form, and felt her body soften in his embrace. The embrace became more urgent and tender, and in the hour of passion that followed, the seed of their first son was sown.