Полная версия

A Student's History of England, v. 1: B.C. 55-A.D. 1509

14. Compurgation and Ordeal.—A new difficulty was introduced when a person who was charged with crime denied his guilt. As there were no trained lawyers and there was no knowledge of the principles of evidence, the accused person was required to bring twelve men to be his compurgators—that is to say, to hear him swear to his own innocence, and then to swear in turn that his oath was true. If he could not find men willing to be his compurgators he could appeal to the judgment of the gods, which was known as the Ordeal. If he could walk blindfold over red-hot ploughshares, or plunge his arm into boiling water, and show at the end of a fixed number of days that he had received no harm, it was thought that the gods bore witness to his innocency and had as it were become his compurgators when men had failed him. It is quite possible that all or most of those who tried the ordeal failed, but as nobody would try the ordeal who could get compurgators, those who did not succeed must have been regarded as persons of bad character, so that no surprise would be expressed at their failure.

15. Punishments.—When a man had failed in the ordeal there was a choice of punishments. If his offence was a slight one, a fine was deemed sufficient. If it was a very disgraceful one, such as secret murder, he was put to death or was degraded to slavery, in most cases he was declared to be a 'wolf's-head'—that is to say, he was outlawed and driven into the woods, where, as the protection of the community was withdrawn from him, anyone might kill him without fear of punishment.

16. The Folk-moot.—As the hundred-moot did justice between those who lived in the hundred, so the folk-moot did justice between those who lived in different hundreds, or were too important to be judged in the hundred-moot. The folk-moot was the meeting of the whole folk or tribe, which consisted of several hundreds. It was attended, like the hundred-moot, by four men and the reeve from each township, and it met twice a year, and was presided over by the chief or Ealdorman. The folk-moot met in arms, because it was a muster as well as a council and a court. The vote as to war and peace was taken in it, and while the chief alone spoke, the warriors signified their assent by clashing their swords against their shields.

17. The Kingship.—How many folks or tribes settled in the island it is impossible to say, but there is little doubt that many of them soon combined. The resistance of the Britons was desperate, and it was only by joining together that the settlers could hope to overcome it. The causes which produced this amalgamation of the folks produced the king. It was necessary to find a man always ready to take the command of the united folks, and this man was called King, a name which signifies the man of the kinship or race at the head of which he stood. His authority was greater than the Ealdorman's, and his warriors were more numerous than those which the Ealdorman had led. He must come of a royal family—that is, of one supposed to be descended from the god Woden. As it was necessary that he should be capable of leading an army, it was impossible that a child could be king, and therefore no law of hereditary succession prevailed. On the death of a king the folk-moot chose his successor out of the kingly family. If his eldest son was a grown man of repute, the choice would almost certainly fall upon him. If he was a child or an invalid, some other kinsman of the late king would be selected.

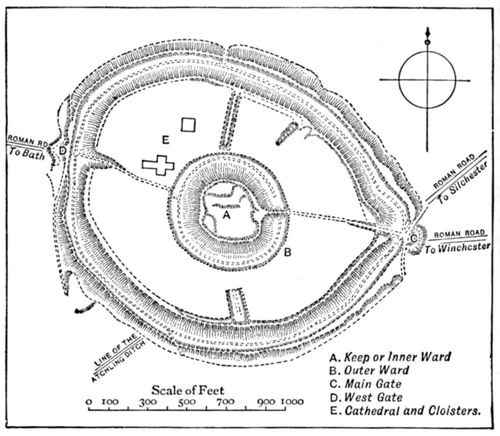

18. The Legend of Arthur.—Thirty-two years passed away after the defeat of the West Saxons at Mount Badon in 520 (see p. 28) before they made any further conquests. Welsh legends represent this period as that of the reign of Arthur. Some modern inquirers have argued that Arthur's kingdom was in the north, whilst others have argued that it was in the south. It is quite possible that the name was given by legend to more than one champion; at all events, there was a time when an Ambrosius, probably a descendant of Ambrosius Aurelianus (see p. 27), protected the southern Britons. This stronghold was at Sorbiodunum, the hill fort now a grassy space known as Old Sarum, and his great church and monastery, where Christian priests encouraged the Christian Britons in their struggle against the heathen Saxons, was at the neighbouring Ambresbyrig (the fortress of Ambrosius), now modernised into Amesbury. Thirty-two years after the battle of Mount Badon the kingdom of Ambrosius had been divided amongst his successors, who were plunged in vice and were quarrelling with one another.

Plan of the city of Old Sarum, the ancient Sorbiodunum. The Cathedral is of later date.

19. The West Saxon Advance.—In 552 Cynric, the West Saxon king, attacked the divided Britons, captured Sorbiodunum, and made himself master of Salisbury Plain. Step by step he fought his way to the valley of the Thames, and when he had reached it, he turned eastwards to descend the river to its mouth. Here, however, he found himself anticipated by the East Saxons, who had captured London, and had settled a branch of their people under the name of the Middle Saxons in Middlesex. The Jutes of Kent had pushed westwards through the Surrey hills, but in 568 the West Saxons defeated them and drove them back. After this battle, the first in which the conquerors strove with one another, the West Saxons turned northwards, defeated the Britons in 571 at Bedford, and occupied the valleys of the Thame and Cherwell and the upper valley of the Ouse. They are next heard of much further west, and it has been supposed that they turned in that direction because they found the lower Ouse already held by Angle tribes. However this may have been, they crossed the Cotswolds in 577 under two brothers, Ceawlin and Cutha, and at Deorham defeated and slew three kings who ruled over the cities of Glevum (Gloucester), Corinium (Cirencester), and Aquæ Sulis (Bath). They seized on the fertile valley of the Severn, and during the next few years they pressed gradually northwards. In 584 they destroyed and sacked the old Roman station of Viriconium. This was their last victory for many a year. They attempted to reach Chester, but were defeated at Faddiley by the Britons, who slew Cutha in the battle.

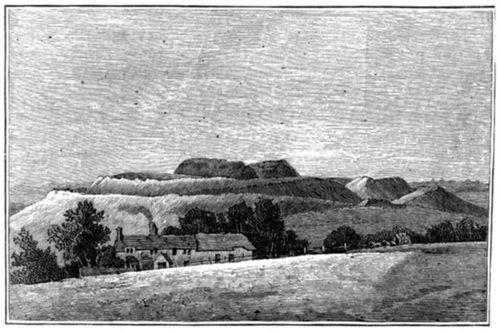

Old Sarum from an engraving published in 1843, showing mound. (It is now obscured by trees from this point of view.)

20. Repulse of the West Saxons.—After the defeat at Faddiley the West Saxons split up into two peoples. Those of them who settled in the lower Severn valley took the name of Hwiccan, and joined the Britons against their own kindred. This alliance could hardly have taken place if the Hwiccan, in settling in the Severn valley, had destroyed the whole, or even a considerable part, of the Celtic population, though there can be little doubt that there was still slaughter when a battle was fought or a town taken by storm; as it is known that the magnificent Roman buildings at Bath were standing in ruins and the city untenanted many years after the capture of the city. At all events, the Britons, now allied with the Hwiccan, defeated Ceawlin at Wanborough. After this disaster, though the West Saxon kingdom retained its independence, it was independent within smaller limits than those which Ceawlin had wished to give to it. If he had seized Chester he would have been on the way to gain the mastery over all England, but he had tried to do too much in a short time. His people can hardly have been numerous enough to occupy in force a territory reaching from Southampton Water to Bedford on one side and to Chester on another.

21. The Advance of the Angles.—Whilst the West Saxons were enlarging their boundaries in the south, the Angles were gradually spreading in the centre and the north. The East Anglians were stopped on their way to the west by the great fen, but either a branch of the Lindiswara or some new-comers made their way up the Trent, and established themselves first at Nottingham and then at Leicester, and called themselves the Middle English. Another body, known as the Mercians, or men of the mark or border-land, seized on the upper valley of the Trent. North of the Humber the advance was still slower. In 547, five years before the West Saxons attacked Sorbiodunum, Ida, a chieftain of one of the scattered settlements on the coast, was accepted as king by all those which lay between the Tees and the Forth. His new kingdom was called Bernicia, and his principal fortress was on a rock by the sea at Bamborough. During the next fifty years he and his successors enlarged their borders till they reached that central ridge of moorland hill which is sometimes known as the Pennine range. The Angles between the Tees and the Humber called their country Deira, but though they also united under a king, their progress was as slow as that of the Bernicians. Bernicia and Deira together were known as North-humberland, the land north of the Humber, a much larger territory than that of the modern county of Northumberland.

22. The Kymry.—It is probable that the cause of the slow advance of the northern Angles lay in the existence of a strong Celtic state in front. Welsh tradition speaks of a ruler named Cunedda, who after the departure of the Roman legions governed the territory from the Clyde to the south of Wales, which formed the greater part of what had once been known as Upper Britain. (See p. 25.) This territory was inhabited by a mixed population of Britons and Goidels, with an isolated body of Picts in Galloway. A common danger from the English fused them together, and as a sign of the wearing out of old distinctions, they took the name of Kymry, or Comrades, the name by which the Welsh are known amongst one another to this day, and which is also preserved in the name of Cumberland, though the Celtic language is no longer spoken there.

23. Britain at the End of the Sixth Century.—During the sixth century the Kymry ceased to be governed by one ruler, but the chieftains of the various territories all acknowledged the supremacy of a descendant of Cunedda. For purposes of war they combined together, and as the country which they occupied was hilly and easily defended, the northern English discovered that they too must unite amongst themselves if they were to overpower the united resistance of the Kymry.

CHAPTER III.

THE STRIFE OF THE ENGLISH KINGDOMS

LEADING DATESAugustine's mission 597

Æthelfrith's victory at Chester 613

Penda defeats Eadwine at Heathfield 633

Penda's defeat at Winwæd 655

Theodore Archbishop of Canterbury 668

Offa defeats the West Saxons at Bensington 779

Ecgberht returns to England 800

Death of Ecgberht 839

1. England and the Continent.—Whatever may be the exact truth about the numbers of Britons saved alive by the English conquerors, there can be no doubt that English speech and English customs prevailed wherever the English settled. In Gaul, where the German Franks made themselves masters of the country, a different state of things prevailed. Roman officials continued to govern the country under Frankish kings, Roman bishops converted the conquerors to Christianity, and Roman cities maintained, as far as they could, the old standard of civilisation. All commercial intercourse between Gaul, still comparatively rich and prosperous, and Britain was for some time cut off by the irruption of the English, who were at first too rude and too much engaged in fighting to need the products of a more advanced race. Gradually, however, as the English settled down into peaceful industry along the south-eastern shores of the island, trade again sprang up, as it had sprung up in the wild times preceding the landing of Cæsar. The Gaulish merchants who crossed the straits found themselves in Kent, and during the years in which the West Saxon Ceawlin was struggling with the Britons the communications between Kent and the Continent had become so friendly that in 584, or a little later, Æthelberht, king of Kent, took to wife Bertha, the daughter of a Frankish king, Charibert. Bertha was a Christian, and brought with her a Christian bishop. She begged of her husband a forsaken Roman church for her own use. This church, now known as St. Martin's, stood outside the walls of the deserted city of Durovernum, the buildings of which were in ruins, except where a group of rude dwellings rose in a corner of the old fortifications. In these dwellings Æthelberht and his followers lived, and to them had been given the new name of Cantwarabyrig or Canterbury (the dwelling of the men of Kent). The English were heathen, but their heathenism was not intolerant.

2. Æthelberht's Supremacy.—Æthelberht's authority reached far beyond his native Kent. Within a few years after his marriage he had gained a supremacy over most of the other kings to the south of the Humber. There is no tradition of any war between Æthelberht and these kings, and he certainly did not thrust them out from the leadership of their own peoples. The exact nature of his supremacy is, however, unknown to us, though it is possible that they were bound to follow him if he went to war with peoples not acknowledging his supremacy, in which case his position towards them was something of the same kind as that of a lord to his gesiths.

3. Gregory and the English.—Æthelberht's position as the over-lord of so many kings and as the husband of a Christian wife drew upon him the attention of Gregory, the Bishop of Rome, or Pope. Many years before, as a deacon, he had been attracted by the fair faces of some boys from Deira exposed for sale in the Roman slave-market. He was told that the children were Angles. "Not Angles, but angels," he replied. "Who," he asked, "is their king?" Hearing that his name was Ælla, he continued to play upon the words. "Alleluia," he said, "shall be sung in the land of Ælla." Busy years kept him from seeking to fulfil his hopes, but at last the time came when he could do something to carry out his intentions, not in the land of Ælla, but in the land of Æthelberht. He became Pope. In those days the Pope had far less authority over the Churches of Western Europe than he afterwards acquired, but he offered the only centre round which they could rally, now that the Empire had broken up into many states ruled over by different barbarian kings. The general habit of looking to Rome for authority, which had been diffused over the whole Empire whilst Rome was still the seat of the Emperors, made men look to the Roman Bishop for advice and help as they had once looked to the Roman Emperor. Gregory, who united to the tenderheartedness of the Christian the strength of will and firmness of purpose which had marked out the best of the Emperors, now sent Augustine to England as the leader of a band of missionaries.

4. Augustine's Mission. 597.—Augustine with his companions landed at Ebbsfleet, in Thanet, where Æthelberht's forefathers had landed nearly a century and a half before. After a while Æthelberht arrived. Singing a litany, and bearing aloft a painting of the Saviour, the missionaries appeared before him. He had already learned from his Christian wife to respect Christians, but he was not prepared to forsake his own religion. He welcomed the new-comers, and told them that they were free to convert those who would willingly accept their doctrine. A place was assigned to them in Canterbury, and they were allowed to use Bertha's church. In the end Æthelberht himself, together with thousands of the Kentish men, received baptism. It was more by their example than by their teaching that Augustine's band won converts. The missionaries lived 'after the model of the primitive Church, giving themselves to frequent prayers, watchings, and fastings; preaching to all who were within their reach, disregarding all worldly things as matters with which they had nothing to do, accepting from those whom they taught just what seemed necessary for livelihood, living themselves altogether in accordance with what they taught, and with hearts prepared to suffer every adversity, or even to die, for that truth which they preached.'

5. Monastic Christianity.—These missionaries were monks as well as preachers. The Christians of those days considered the monastic life to be the highest. In the early days of the Church, when the world was full of vice and cruelty, it seemed hardly possible to live in the world without being dragged down to its wickedness. Men and women, therefore, who wished to keep themselves pure, withdrew to hermitages or monasteries, where they might be removed from temptation, and might fit themselves for heaven by prayer and fasting. In the fifth century Benedict of Nursia had organised in Italy a system of life for the monastery which he governed, and the Benedictine rule, as it was called, was soon accepted in almost all the monasteries of Western Europe. The special feature of this rule was that it encouraged labour as well as prayer. It was a saying of Benedict himself that 'to labour is to pray.' He did not mean that labour was good in itself, but that monks who worked during some hours of the day would guard their minds against evil thoughts better than if they tried to pray all day long. Augustine and his companions were Benedictine monks, and their quietness and contentedness attracted the population amidst which they had settled. The religion of the heathen English was a religion which favoured bravery and endurance, counting the warrior who slaughtered most enemies as most highly favoured by the gods. The religion of Augustine was one of peace and self-denial. Its symbol was the cross, to be borne in the heart of the believer. The message brought by Augustine was very hard to learn. If Augustine had expected the whole English population to forsake entirely its evil ways and to walk in paths of peace, he would probably have been rejected at once. It was perhaps because he was a monk that he did not expect so much. A monk was accustomed to judge laymen by a lower standard of self-denial than that by which he judged himself. He would, therefore, not ask too much of the new converts. They must forsake the heathen temples and sacrifices, and must give up some particularly evil habits. The rest must be left to time and the example of the monks.

6. The Archbishopric of Canterbury.—After a short stay Augustine revisited Gaul and came back as Archbishop of the English. Æthelberht gave to him a ruined church at Canterbury, and that poor church was named Christ Church, and became the mother church of England. From that day the Archbishop's See has been fixed at Canterbury. If Augustine in his character of monk led men by example, in his character of Archbishop he had to organise the Church. With Æthelberht's help he set up a bishopric at Rochester and another in London. London was now again an important trading city, which, though not in Æthelberht's own kingdom of Kent, formed part of the kingdom of Essex, which was dependent on Kent. More than these three Sees Augustine was unable to establish. An attempt to obtain the friendly co-operation of the Welsh bishops broke down because Augustine insisted on their adoption of Roman customs; and Lawrence, who succeeded to the archbishopric after Augustine's death, could do no more than his predecessor had done.

7. Death of Æthelberht. 616.—In 616 Æthelberht died. The over-lordship of the kings of Kent ended with him, and Augustine's church, which had largely depended upon his influence, very nearly ended as well. Essex relapsed into heathenism, and it was only by terrifying Æthelberht's son with the vengeance of St. Peter that Lawrence kept him from relapsing also. On the other hand, Rædwald, king of the East Anglians, who succeeded to much of Æthelberht's authority, so far accepted Christianity as to worship Christ amongst his other gods.

8. The Three Kingdoms opposed to the Welsh.—Augustine's Church was weak, because it depended on the kings, and had not had time to root itself in the affections of the people. Æthelberht's supremacy was also weak. The greater part of the small states which still existed—Sussex, Kent, Essex, East Anglia, and most of the small kingdoms of central England—were no longer bordered by a Celtic population. For them the war of conquest and defence was at an end. If any one of the kingdoms was to rise to permanent supremacy it must be one of those engaged in strenuous warfare, and as yet strenuous warfare was only carried on with the Welsh. The kingdoms which had the Welsh on their borders were three—Wessex, Mercia, and North-humberland, and neither Wessex nor Mercia was as yet very strong. Wessex was too distracted by conflicts amongst members of the kingly family, and Mercia was as yet too small to be of much account. North-humberland was therefore the first of the three to rise to the foremost place. Till the death of Ælla, the king of Deira, from whose land had been carried off the slave-boys whose faces had charmed Gregory at Rome, Deira and Bernicia had been as separate as Kent and Essex. Then in 588 Æthelric of Bernicia drove out Ælla's son and seized his kingdom of Deira, thus joining the two kingdoms of Deira and Bernicia (see p. 36) into one, under the new name of North-humberland.2

9. Æthelfrith and the Kymry.—In 593, four years before the landing of Augustine, Æthelric was succeeded by his son Æthelfrith. Æthelfrith began a fresh struggle with the Welsh. We know little of the internal history of the Welsh population, but what we do know shows that towards the end of the sixth century there was an improvement in their religious and political existence. The monasteries were thronged, especially the great monastery of Bangor-iscoed, in the modern Flintshire, which contained 2,000 monks. St. David and other bishops gave examples of piety. In fighting against Æthelfrith the warriors of the Britons were fighting for their last chance of independence. They still held the west from the Clyde to the Channel. Unhappily for them, the Severn, the Dee, and the Solway Firth divided their land into four portions, and if an enemy coming from the east could seize upon the heads of the inlets into which those rivers flowed he could prevent the defenders of the west from aiding one another. Already in 577, by the victory of Deorham (see p. 35), the West Saxons had seized on the mouth of the Severn, and had split off the West Welsh of the south-western peninsula. Æthelfrith had to do with the Kymry, whose territories stretched from the Bristol Channel to the Clyde, and who held an outlying wedge of land then known as Loidis and Elmet, which now together form the West Riding of Yorkshire.

10. Æthelfrith's Victories.—The long range of barren hills which separated Æthelfrith's kingdom from the Kymry made it difficult for either side to strike a serious blow at the other. In the extreme north, where a low valley joins the Firths of Clyde and Forth, it was easier for them to meet. Here the Kymry found an ally outside their own borders. Towards the end of the fifth century a colony of Irish Scots had driven out the Picts from the modern Argyle. In 603 their king, Aedan, bringing with him a vast army, in which Picts and the Kymry appear to have taken part, invaded the northern part of Æthelfrith's country. Æthelfrith defeated him at Degsastan, which was probably Dawstone, near Jedburgh. 'From that time no king of the Scots durst come into Britain to make war upon the English.' Having freed himself from the Scots in the north, Æthelfrith turned upon the Kymry. After a succession of struggles of which no record remains, he forced his way in 613 to the western sea near Chester. The Kymry had brought with them the 2,000 monks of their great monastery Bangor-iscoed, to pray for victory whilst their warriors were engaged in battle. Æthelfrith bade his men to slay them all. 'Whether they bear arms or no,' he said, 'they fight against us when they cry against us to their God.' The monks were slain to a man. Their countrymen were routed, and Chester fell into the hands of the English. The capture of Chester split the Kymric kingdom in two, as the battle of Deorham thirty-five years before had split that kingdom off from the West Welsh of the south-western peninsula. The Southern Kymry, in what is now called Wales, could no longer give help to the Northern Kymry between the Clyde and the Ribble, who grouped themselves into the kingdom of Strathclyde, the capital of which was Alcluyd, the modern Dumbarton. Three weak Celtic states, unable to assist one another, would not long be able to resist their invaders.