Полная версия

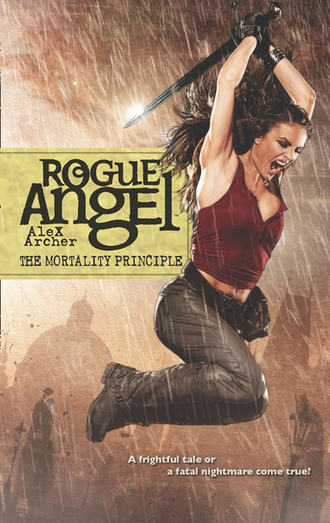

The Mortality Principle

“Fear not, you bought me with coffee.” Annja raised her cup as though toasting the astronomer, and took another gulp. “The show’s never been about tarnishing someone’s reputation, living or dead.”

“I’m glad to hear it,” the woman said, the concern that had begun to build up on her face melting away.

Which of course only served to make Annja wonder if that meant Kepler had a secret worth hiding. But that was just the way her mind worked.

“So, inspiration…”

“Indeed,” said Annja. “Inspiration.”

“Finish your coffee and I’ll give you the grand tour.”

Annja took another sip, surprised that the woman had already finished hers, and then offered the mug back with half of the black treacle still in the bottom.

“That’s the best part,” the woman said, taking it and putting it next to her own like paperweights atop the bundle of papers. “Let’s make a start, then, shall we?”

Annja followed her around, listening to one explanation after another. The woman was a wealth of information when it came to the twelve years Kepler had spent in the city. Annja didn’t hear anyone else enter the building during the hour they walked between display cases, moving from room to room. She wondered how many visitors the museum received every day. It was getting on toward lunchtime, or at least brunch, so the tourists were no doubt still enjoying a leisurely stroll around the town, waiting for the hour to chime and the figures of the astronomical clock to do their macabre dance come midday. Perhaps more would come by in the afternoon. Or had people stopped caring about men like Johannes Kepler and all that they had done to further humankind’s understanding of the world?

She listened attentively, and it was obvious that much of the talk was stuff the woman had learned by rote and recited many times each week. It covered most of Kepler’s scientific achievements and the contributions that his studies had made to the science of astronomy. It was interesting, but it wasn’t show material. She’d already begun to forget some of the opening facts and she hadn’t even walked out the door.

She concentrated on what the woman had to say about his involvement with the city itself, but there was very little of that in her prepared speech.

As they approached the end of the tour, Annja knew as much as anyone could possibly ever want to know about the astronomer, but there’d been nothing to send a shiver up her spine. Nothing that told her she was listening to a story that would be worth chasing.

“A few of the places connected to Kepler are still standing,” the woman said. “Obviously you’re standing in one of them, but there are a few others worth taking a look at, if you are interested.”

Annja said she was. “Where would you recommend?”

“You might like to take a trip out to Benátky nad Jizerou if you’re taking a tour of the area. It’s a small town, half an hour away. It was where Tycho Brahe was building his observatory when he invited Kepler to join him. I’ve no idea how much they have there, but the town and the castle are worth visiting.”

Annja had heard the woman mention Brahe several times as they walked through the exhibits. Like Kepler, Brahe had been an important figure in the study of the planets at the time. Although his name hadn’t left such a lasting global legacy, he had clearly been an instrumental figure in the foundation of Prague as a center for scientific thought.

“I might just do that,” Annja said. “Thanks.”

They headed toward the door, making small talk as they took the wooden stairs back down to the street level. It had been an interesting way to pass an hour or so, but it hadn’t solved Annja’s problem, and as far as she could see there was nothing pointing her in the direction of the next story.

“It’s been lovely to meet you,” the woman said as they reached the door. She made a show of looking up and down the street and shaking her head. “I’m starting to think that you might be our only visitor today.”

“Things are that bad?”

“Worse,” she said.

“How come?”

Annja’s first thought was that the place wasn’t making itself visible enough. After all, it was hidden away, and failing to appeal to the young. But then Prague was more commonly thought of as a party city where visitors could leave behind the consequences of their actions, not the kind of place you came to soak in the legacy of almost-forgotten scientists. That being the case, no amount of glossy brochures or clever marketing gimmicks would help.

She’d jumped to the wrong conclusion.

“It’s the murders,” the woman said. “You can hardly blame people for keeping away, I suppose. Who wants to go wandering around when people are getting murdered right outside their front doors? So, we struggle, and if the police don’t find the killer soon, it will be too late for some of us.”

“Is it really that bad?” Annja asked.

She’d been in Prague nearly a week and had been so wrapped up in her own problems she hadn’t even noticed. That was what Garin meant about living in the real world for a while.

She avoided mentioning just how close she might have come to the killer, hoping that the woman would fill in some of the details Garin had hinted at over breakfast.

“Oh, yes. There have been several of them. Poor homeless people found dead in alleyways and parking lots. Some huddled in doorways, their blankets still drawn up under their chins as if they were just sleeping.” The way the woman talked about it, it sounded like there were far more than four dead bodies that had been accounted for.

“Are the victims always homeless?”

The woman nodded. “Yes. Every one of them. There’s nothing to say that ordinary people like you or me are at risk, but it has put people off coming into the city. The hotels are half-full where usually they’d be booked up at this time of year. It’s worrying.”

“I’ve been here a week and I didn’t even know about the murders until this morning,” Annja admitted. “Not that it would have made much difference if I had known. My bosses wouldn’t have let me duck out of this trip. The way things are back home, I think they’d probably like it if I came face-to-face with the killer. Better for the ratings than another show about the golem.”

“I’ve never understood why everyone is obsessed with that story,” the woman said. “It’s just a fairy tale. One of the newspapers keeps trying to link the killings with that old story, too. They’re willing to do anything to sensationalize the whole thing.” She shook her head sadly. “If you ask me, they’d be better off getting people to help find the killer or putting their efforts into making sure those poor souls had some kind of shelter for the night.”

Which, Annja knew, was not merely true; it was obvious. If a killer was targeting the homeless, the very best thing the city could do to protect its people was to see that they had somewhere to sleep that was safe. But it was also obvious, from a narrative point of view, for the journalists to build up a story that linked real life events to the myth. Myths had power—power to thrill, power to chill. Telling the story would not only increase the sense of fear gripping the city, but it would sell newspapers. And, judging by the suits back home, that was the only thing that mattered to some people.

She gave her thanks to her guide, accepting a couple of brochures that the woman offered her, and highlighted the village that she had suggested Annja visit. Annja slipped them in her bag and pulled out a twenty-euro note. The woman tried to wave it away, but Annja insisted on leaving it as a donation. If things were as bad as they seemed to be, there was no way that the woman could afford to refuse any money coming her way. Despite protesting, the woman put it into the donations jar beside the door.

Annja stepped out into the street.

She felt the warmth on her face that had been missing inside the building.

She might not have found anything new relating to her story, but she might just have stumbled onto the obvious angle for the story she had. People’s macabre fascination with murder sold newspapers. And if it was good enough to sell newspapers, then it ought to be good enough for the network’s suits. But would it be good enough to save Chasing History’s Monsters?

Only time would tell.

4

A quick visit to the newsstand confirmed which newspaper had been carrying the stories that connected the vagrant murders with Rabbi Loew’s golem.

Even though the words were incomprehensible, the front page of one of the papers in the newsstand’s racks carried Loew’s name and an etching in place of a photograph that detailed the golem’s nighttime wandering through these streets. Unable to read it, she decided she needed a different course of action. Thinking on her feet, Annja noted the name of the reporter whose byline appeared underneath the headline: Jan Turek.

A call to the newspaper resulted in her being passed from person to person until someone was found who spoke a language they had in common comfortably enough to answer a few questions. Then she discovered that Turek wasn’t on the staff at all, but was a freelancer, and the staff member was unwilling to pass on any contact details for him without knowing more about her and her credentials. She provided Doug Morrell’s contact information and told the staffer he could check in with him. She hoped that being on staff with a cable television corporation in the US would be enough to persuade them to put her in touch with Turek. She gave the staffer her number at the hotel and returned there to wait for Doug to confirm she was who she said she was.

When the phone rang she snatched it up and answered.

It wasn’t Jan Turek.

It was the staffer, who confirmed that Doug Morrell had vouched for her, though he hadn’t appreciated being woken up at six in the morning. Annja couldn’t help herself, she laughed at that, having completely forgotten about the time difference when she’d given the staffer Doug’s cell number. The woman promised to take a message and pass it on to Turek, but couldn’t promise when he’d get back to her.

“He’s not exactly the most reliable soul,” she explained. “Which is why he’s not on the staff here. But I’ll call him now and leave your message. He’s more of a night bird,” the woman said, which Annja immediately corrected to night owl in her mind. “I think he sleeps for most of the day, so don’t expect a call back from him for a while.”

“But he’s definitely the man I need to speak to about the stories you’ve been running about the killings?”

“Oh, yes. Can I ask, are you looking to buy the story from Jan?”

“It’s possible,” Annja said. She knew how papers worked. The reporter would have a lot of material that hadn’t made it into the finished copy. Was there anything in there that would be of interest to her? Maybe.

“I’ll make sure I tell him that. He’s more likely to give you a call if there’s a chance of money changing hands. You know how these freelancers are. If you don’t hear from him, you might want to check out some of the places where people sleep outside. He’s been talking to a lot of the homeless people late at night. I think he’s even slept on the streets himself a couple of nights this week in the hope that he might catch the killer himself. The police warned him off that, though, so hopefully he listened to them. To be honest, I don’t like the idea of him out there. It’s not safe.”

“Thanks,” Annja said.

If the man didn’t call her back, she was going to have to go looking for him, but she would have somewhere to start, which was more than she’d had an hour ago. How many Jan Tureks could there be in the city?

She was more than capable of looking after herself no matter who she found herself up against. But it was still seven or eight hours until it would start to get dark, and another six or seven until it was the right time to go hunting the killer, which made as much sense as hunting for the journalist who was writing about him.

That meant she was at a loose end.

She had time to kill.

She had exhausted the research she had brought with her three times over, but now she had another angle to chase. She decided to check the internet to see if there were better reports about the killings that had made it into the international press. Worst case, she could run Turek’s reports—assuming they were online—through a translation app and at least get some sort of idea what theories he was putting forward. It wouldn’t hurt to know just how much fear he was causing with his pieces, either. That was where the comments sections came in.

She headed back to the hotel, assuming Garin would still be occupying himself for a while yet.

From outside, the hotel was an unassuming building. It had been a Dominican monastery back in the golem’s day. Now it offered her space for quiet contemplation. Both the businessmen and the tourists had long since left, leaving the foyer empty. Annja walked toward the desk, which was between her and the single flight of stairs that led to the first floor where her room was. The receptionist looked up and smiled, returning to her work when Annja turned toward the stairs.

A middle-aged couple talking rapidly in German emerged from the stairway and walked straight to the reception desk without giving her a second glance.

Annja climbed the stairs two at a time, eager to get to work now that she had something to focus on.

She passed Garin’s room, hearing voices behind the door. No doubt he was charming the waitress with talk of his jet airplane and a trip to Paris for champagne and strawberries that evening. That was his usual technique when it came to sweeping women off their feet: leave them dizzy with the heady rush of a life barely even imagined. If not Paris, maybe it would be pizza in Rome or Venetian ice cream, gazing out over the Lido. How many times in the past few years had Garin tried to impress her the same way? More than enough was the answer, though in truth he’d never impressed her more than that very first time they’d come face-to-face as she hunted the Beast of Gévaudan. He’d saved her life that day. To Annja’s way of thinking that was more impressive than traveling half the world to dine at some fancy five-star restaurant, but as she’d quickly come to learn she was pretty much one of a kind.

She smiled to herself as she moved on to her own room.

5

Two hours sped by with Annja reading the various reports. It wasn’t easy, the language barrier present even online, but she managed to track down more and more articles on the internet—though, painfully, as the translation site had a habit of turning the original Czech articles into gibberish.

She could have taken them to a translation service, but that would take time and cost money and probably only serve to annoy her paymasters. Or she could have asked around for a person who was fluent in English—fluent enough to give her a real idea of just how emotive the language in the articles was.

Of course, she had an ace up her proverbial sleeve. Roux. The man knew so much and had seen so much more. Even if he didn’t have the answers, he would know someone who did. And in this case, he had no agenda, no wish to gain anything from her requests for help. That was the primary difference between the old man and Garin. Garin was like the song: he was his first, his last, his everything. He always put the interests of Garin Braden ahead of the interests of others. It wasn’t just about being selfish, it was about being himself. You didn’t live six hundred years of decadence without picking up some bad habits along the way. It was only inevitable that centuries of getting neck-deep in fecal matter and somehow emerging smelling of roses gave you a warped perspective on life. Roux was different. She didn’t know why—on a fundamental level—that should be so. But it was. The only thing she’d noticed, and it was through years of quiet observation as opposed to direct confrontation, was that Roux welcomed the idea that he might not live forever whereas Garin dreaded it.

The old man might come across as cantankerous at the best of times, but he was the rock she could rely on while all else around her floundered. And he wouldn’t ask for anything else in return, even if he wasn’t completely enthusiastic about getting involved. That was another sign that age was catching up with him. She’d noticed it time and again since what had felt like Garin’s ultimate betrayal beneath the Pass of the Moor’s Sigh. He’d taken that hard. It wasn’t just that Garin had shown his true colors; it was that maybe, just maybe, Roux had finally accepted that he couldn’t change his former apprentice’s nature.

She played with the phone for a moment. Roux was the touchstone that linked both of the lives she lived. He was a constant in an ever-changing world.

She punched in his number and waited for the phone to ring.

“To what do I owe this pleasure, my dear?” the old man said. There was no hint of surprise in Roux’s voice.

“How are you doing?”

“Much the same as I am always doing,” the old man replied. “As wonderful as it is to hear from you, I take it this isn’t a social call? What can I do for you?”

“How good is your Czech?”

“Written or spoken?”

“Written,” she said, unsurprised that he’d made the distinction rather than dismiss her question straightaway.

“Fair,” he said. “As long as it’s not too technical. What are we talking about?”

“A few tabloid articles. I’m sending you the links now.”

“I didn’t say that I was going to help you,” Roux chided lightly. “Sometimes you take things for granted.”

“You also didn’t say you weren’t going to help me,” she said, wishing that he would be a little more obvious when he was feeling prickly. Some sort of code word would save a lot of misunderstanding. “Let’s try again. Will you help me? Pretty please, O great and powerful Roux?”

There was an audible sigh that he exaggerated for her benefit, which guaranteed he’d read the articles for her.

“All right. Send the links. I’ll call you back once I’ve had the chance to digest them. I assume we aren’t looking at War and Peace here? I have a busy day ahead of me.”

“There shouldn’t be too much,” Annja said. “I’m only interested in the pieces that refer to the golem.”

“The golem?”

“Yeah, you know, Rabbi Loew… The Golem of Prague…”

“I’m not a simpleton, Annja, I know exactly what you’re talking about. I just don’t understand what your interest in it might be. After all, it’s a fairy tale.” He paused for a moment. There was an anguished tone lurking beneath his voice when he continued. “I’ve always thought that you considered what you do to be a proper job. Something worthwhile. Not frivolity. Was I wrong?”

Annja didn’t think she’d ever heard him use those kinds of words to describe what she did. “There’s a story here. It’s something that viewers might be interested in, yes, but it’s more than that. If I didn’t know better, I’d think you were deliberately being antagonistic. This isn’t like you. So I’m just going to ignore it. I refuse to rise to the bait.”

“Not antagonistic, merely surprised.” She heard the tap of keys as Roux followed up the links to the web-pages she had sent him. “There’s quite a bit here,” he said after another minute or so. “I’ll call you in half an hour.” He hung up without waiting for her response.

It wasn’t the first time he had done that to her, and odds were it wouldn’t be the last. With half an hour to kill, she carried on scrolling through everything she could find about the recent spate of killings in the city while she watched the seconds crawl by. Once upon a time losing herself like Alice down the rabbit hole of the internet could have swallowed thirty minutes in the blink of an eye. All she had to do was follow a link, then another that branched off from the first toward something vaguely interesting, and then another, and suddenly half the day was gone. It wasn’t like that now. Now every second dragged and every link offered frustration.

Even so, fifteen minutes had been wasted by the time her phone rang.

Roux’s name flashed on the screen.

“That was quick,” she said, after snatching it up.

“Some things don’t take long to read,” the old man said. His voice had changed in the few minutes since he’d hung up on her. She knew him well enough to know that meant something was wrong.

“Talk to me. What do you think?”

He waited a moment, as though weighing up what, precisely, to say to her. Finally he said, “I think you might be getting caught up in something you don’t understand.” It was blunt and to the point. And it meant there was no way she was walking away from this now. Because, as well as she knew him, the old man knew her, too. He knew exactly what to say to plant the seed that would grow into obsession.

“I know what you’re doing,” she said. “You’re not the kid-gloves kind of guy. Spill.”

She could hear the smile in his voice. “I was merely observing that this might not be as simple as it seems.”

“And you know what it’s like when you dangle imminent danger in front of me,” Annja said. “I can’t resist.”

“I know, but that doesn’t mean I wouldn’t rather your television show had taken you somewhere else, just this once.”

“So, what do they say?”

“Ostensibly they cover a spate of murders in the Czech capital, and the journalist who wrote these articles—Jan Turek—has found a way of linking them to the legend of the golem. But this, I suspect, you already know.”

“I do. It’s why I sent you them.”

“Almost everything in Prague can be linked to the legend in some way, Annja. It is a city filled with hidden dangers. Most of the time they stay hidden, but every now and then one of them finds its way out into the daylight.”

“What does it say, Roux? I’m a big girl. I can look after myself.”

“Just that Turek believes some ancient evil has stirred. I want you to promise me you won’t do anything stupid, Annja.”

“I can’t promise that,” she said, trying her best to sound light and breezy rather than like some petulant teenager. “Anyway, it’s not like I’m on my own.”

“I don’t think that cameraman of yours is likely to be much help.”

“I’m not talking about Lars. Garin turned up this morning.”

“Garin? What on earth is he doing there?” Roux asked. Annja noted the change in his voice. It was more than just the mention of Garin’s name. Maybe, she surmised, it was even part of the reason why he was here in Prague.

“Did he say why he wanted to see you?” Roux asked, following an identical train of thought.

“No. He made out that he was bored. And to be brutally honest, he seemed intent on relieving that boredom with the waitress who served us breakfast.” She expected some kind of response from Roux, some barbed comment about the younger man’s proclivities, some damning indictment of his lifestyle. None came.

Instead, he said, “If we’re going to do this, we’re going to do it properly. I’m coming. Don’t go out after sunset. I’ll be there in a few hours.”

“Roux?” Something really had him spooked. “You don’t have to.”

“I do. Believe me. There are things about that city you don’t understand. Ancient forces. Evil. I am not leaving you alone there.”

“Okay, Roux, now you’re scaring me.”

“Good. It’s good to be scared.”

“Should I warn Garin?”

“He went there with his eyes open. He almost certainly knows what these murders mean. He isn’t a fool, and to use one of your own rather eloquent turns of phrase, he’s big enough and ugly enough to take care of himself. I have a few things to take care of, but I’ll be with you before sunrise. In the meantime, do not go out after dark. Promise me.”

“I promise,” Annja said, knowing it was a promise she was absolutely going to break, but promising it, anyway.

He hung up on her again. Twice within the hour, now that was almost a record.