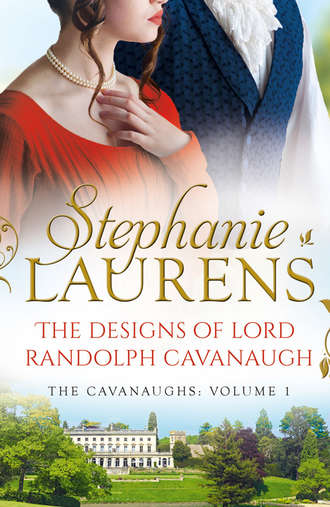

The Designs Of Lord Randolph Cavanaugh: #1 New York Times bestselling author Stephanie Laurens returns with an uputdownable new historical romance

Полная версия

The Designs Of Lord Randolph Cavanaugh: #1 New York Times bestselling author Stephanie Laurens returns with an uputdownable new historical romance

Жанр: любовные романысовременные любовные романыисторическая литературасовременная зарубежная литературасерьезное чтениеоб истории серьезно

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2018

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу