Полная версия

Collins New Naturalist Library

Key to species

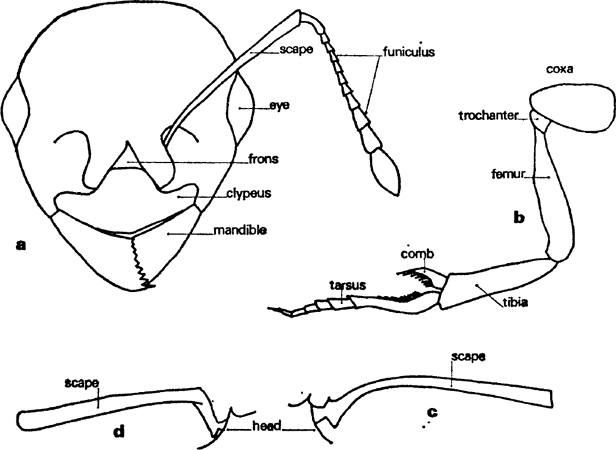

AMyrmicaOScape of antenna near point of attachment to head bent gradually and smoothly without ridges; head relatively shiny, especially the frontal area (fig. 6c)1—Scape bent sharply through a right angle, with or without ridges, head dull, matt (fig. 6d)21Epinotal spines long in relation to body size; either workers large, queens larger than workers, fewer than 10 in a colony (macrogyna)orqueens same size as workers, more than 10 in a colony (microgyna)ruginodis—Epinotal spines short in relation to body size; workers small, queens much larger, up to 100 in a colonyrubra2Antennal scape without ridge or teeth; frontal area with marked striations; a dark ant in moorlandsulcinodis—Antennal scape with ridges or teeth at the bend33Scape with very characteristic transverse ridge or plate at bend, almost tooth-like from some aspects; a small, dark specieslobicornis—Scape with lateral ridge at bend, reddish-brownscabrinodis(fig. 6d) andsabuleti

FIG. 6. Worker of Myrmica rubra: a. head, b. foreleg, c. scape of antenna, d. Myrmica scabrinodis: scape of antenna. c. and d. are viewed from behind. Hairs are abundant on the head which is strongly corrugated.

scabrinodis is a smaller ant and has a less pronounced lateral ridge than sabuleti; it also has more queens in each colonyBLeptothoraxOAntennae with 11 segments; a relatively large speciesacervorum—Antennae with 12 segments; a relatively small species1IClub of funiculus no darker than the rest of the antenna; a distinct dorsal groove or depression across the middle of the mesosoma; nests in tree stumps and woodnylanderi—Club of funiculus darker than the rest of the antenna; no transverse groove on the mesosoma; rare speciestuberumandinterruptus

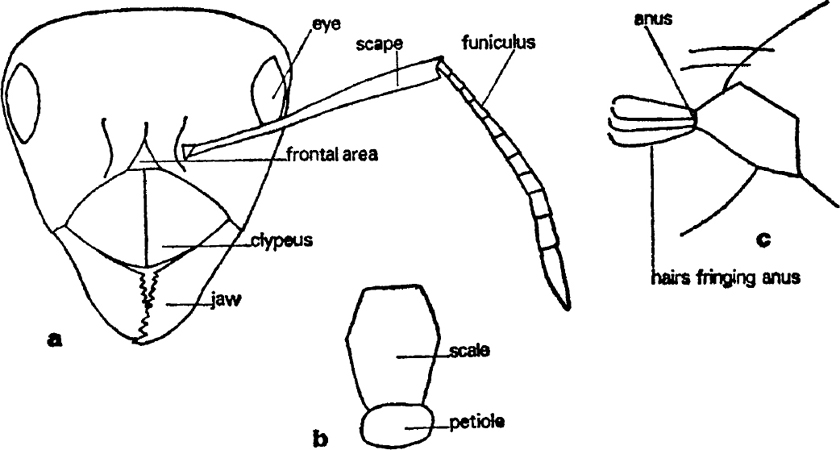

FIG. 7. Worker of Lasius niger: a. head; b. scale on petiole from behind; c. side view of tail segments to show ring of hairs around the circular orifice. The whole body is covered with a light pubescence and there are short, erect hairs on the scape of the antenna but none of these have been shown.

CLasiusOColour jet black, shiny, head heart-shapedfuliginosus—Colour otherwise, head normal11Colour brown to dull black2—Colour yellow42Scape of antenna and tibia of leg with short, upright hairs; body dark, almost black but hairy and mattniger—No such hairs; body browner, less hairy33Frontal area indistinct; smaller, uniformly coloured, individuals living in open, sunny placesalienus—Frontal area distinct; larger individuals with gaster and head darker than the thorax; living in old treesbrunneus4Scape of antenna and tibia of leg with short, upright hairsumbratusandrabaudi—No such hairs55Hairs on top of gaster short, scale tapered abovemixtus—Hairs on top of gaster long, scale broad and low, not tapered above, no cheek hairs in front view; makes soil mounds in grasslandflavusThree of the yellow species, umbratus, rabaudi and mixtus, are very variable and intergrade in the worker caste.DFormicaOClypeus with central notch in lower margin; colour usually deep redsanguinea—Clypeus without notch; colour reddish-brown to blackI1Back of head and top of scale notchedexsecta—Not so22Thorax reddish-brown, paler than head and gaster3—Body black all over63Eyes with small hairs and back of head with prominent long hairs; wood ants making mound nests of vegetation near trees or in open moorland in northern Britain4—Eyes and back of head bare54Thorax with many fine, long hairslugubris—Thorax with fewer, shorter hairsaquilonia5Frontal area shiny, maxillary palp short and hairy; southern wood ants making large mound nests in open forestrufa—Frontal area dull; individuals smaller, making very small mound nests or excavations in open, heathy placescunicularia6Body shiny, black; building small vegetation mounds in wet heath and bogtranskaucasica—Body dull, black; excavating nests in drier placeslemaniandfuscaCHARACTERISTICS AND DISTRIBUTION

Only four of the nine or so sub-families of the family Formicidae are represented in this country. Two of these, Ponerinae and Dolichoderinae, have only one genus here. Of the other two the Myrmicinae have ten and the Formicinae two genera. The Ponerinae and Myrmicinae have certain similarities and are grouped together in a poneroid complex whereas the Dolichoderinae and Formicinae are included in a myrmecoid complex (named after the basic Australian sub-family Myrmeciinae).

The Ponerinae contain a mixture of very primitive and highly-evolved forms which are mainly tropical and Australian in distribution. In southern Europe there are at present some nine species but fossil evidence shows that there were once many more. Primitive features are the possession of a sting in the females (as in wasps) and the structural similarity between queens and workers; the latter lack only wings and ocelli. All ponerines have a constriction between the first and second segments of the gaster; here the integument forms, on the underside, an organ for stridulating. They feed largely on small animals and show foraging behaviour that ranges from the highly individual to the advanced legionary type. Larvae are able to eat prey directly and even to move about the nest slightly in the less advanced genera.

Ponera coarcta has a worldwide distribution but occurs in only 13 of the 152 vice-counties of the British Isles, all in southern England. Its colonies are small and inconspicuous and usually live in woodland amongst the stones and moss of the soil surface. There is another species, Hypoponera punctatissima, that is commonly found in glasshouses and, very rarely, in sunny situations outside.

The Myrmicinae are thought to have evolved from ponerine ants; both groups retain stings and have a tendency to a thick, wrinkled cuticle with spines on the mesosoma. The myrmicine workers have a much simpler and smaller form than the queens. Their waist comprises two segments; this waist gives extraordinary flexibility to the gaster, and enables the sting at its tip to be brought round under the body and pushed forwards in front of the head. The integuments of the second waist on the first gastral segments form a stridulatory organ on the upper side instead of the underside, as in the ponerines. Only in the more primitive genera do the workers lay eggs. Seed-eating is common in this sub-family; it also includes the only group to have perfected a method of culturing and eating fungi. Many genera have evolved social parasitism; of the ten indigenous here half show this tendency.

Undoubtedly the most widespread genus in the British Isles is Myrmica. It is a brownish-red ant found in many different habitats, in small colonies that rarely exceed 3000 workers. They sting effectively and painfully if disturbed. Myrmica reaches into every one of our islands. There are eight species; one, Myrmica ruginodis, is apparently the only ant to have colonized Shetland and the only species so far which has been found in all of the 152 vice-counties. At the opposite extreme there is Myrmica speciodes found only in Kent and Sussex, although it is more common in Europe. This is one genus which shows hardly any geographical bias here, for of the eight species which occur in southern England, six are also found in Scotland.

The next most common genus is Leptothorax, although only one of its four species (Leptothorax acervorum) is widely, though patchily, distributed throughout the British Isles. It is a small, brown ant living in small colonies rich in queens, nesting in quite hard wood or in twigs or under the surface crust of soil. The other three species are restricted to southern England.

Tetramorium caespitum is the only species of this genus (which is predominantly African) in the British Isles. It is a small, black ant spread widely over central Europe but restricted here to the south and farther north to coastal zones. Such habitats have a high incidence of sunshine in spring so that the soil surface where the ants nest is warmed early in the season. Furthermore, temperatures do not fall very much in winter, especially on the western coasts. Tetramorium caespitum makes large, highly-organized colonies in lowland heath in the south. In autumn it collects and stores the seeds of heather and grass for spring feeding.

Two myrmicine genera are parasitic on Tetramorium caespitum in this country. One, Strongylognathus (one species Strongylognathus testaceus), has workers of about the same size and shape as its host but they are pale brown and have curved, toothless mandibles. The sexuals are not much bigger and contrast strikingly with the large black queen of Tetramorium. It is rare, even where it is known to exist in Dorset and Hampshire. The other parasite of Tetramorium is Anergates atratulus. It has no workers and the males are wingless and curiously shaped. Again, this species has only been found in the middle south of England. Very few of the nests of Tetramorium are parasitized; this is so, even in France where both host and parasite are quite widespread.

Stenamma westwoodii is a rare ant limited to the south and rarely seen, even on the Continent. Myrmecina graminicola is a dark, thickset species which nests deep in the soil in sunny places in southern England; sometimes it makes galleries in Myrmica nests where it probably preys on the brood. Formicoxenus nitidulus is a small ant with a highly polished cuticle and lives in nests with wood ants. Solenopsis fugax is a small, yellow ant living underground near Lasius or Formica nests, eating their brood; it is restricted to the south in this country. Finally comes a completely parasitic, workerless species, Sifolinia karavajevi, only recently found here in a colony of Myrmica sabuleti. Emery first caught a female flying near Siena in 1907. The species has been found in Europe and Algeria on a few occasions but the number of colonies parasitized by species of Sifolinia in the whole hemisphere must be remarkably small.

Next are the two myrmecoid sub-families, Formicinae and Dolichoderinae. Both have only one joint in the waist which often carries a well-developed scale, particularly in the former sub-family. The gaster is unconstricted and contains no sting. Instead there is a poison apparatus opening in the Formicinae in a circular orifice, usually surrounded by hairs just below the anus. A jet of fluid consisting largely of formic acid can be shot for several centimetres from this after it has been bent round under the mesosoma and directed forwards. The Dolichoderinae do not produce a liquid jet but in most cases a sticky toxic chemical is extruded from their slit-shaped anus. The difference between queens and workers in the Formicinae is considerable, though the workers do lay eggs in some genera and may produce females as well as males from unfertilized eggs. Other primitive features are the retention of a cocoon to enclose the pupa, the presence of visible ocelli in workers (in some genera) and the incompletely-fused mesosomal sutures. Often, too, they are highly individual and forage singly. Most seem to have a well-developed valve between the crop where imbibed food is stored before regurgitation to larvae and the midgut where food is digested. This is kept closed by the presence of fluid in the crop and does not need a persistent muscular effort, as it is thought to do in the Myrmicinae. Often these ants have quite good vision through the usual insect compound eyes but some species rely entirely on chemical and tactile senses. All make use of nectar and honeydew as well as hunting prey but they do not appear to eat seeds very much (unless these have an oily caruncle).

There are only two genera of formicine ants represented in the British Isles, Lasius and Formica. Lasius are smaller than Formica and have less well-developed eyes. They form a large, diverse genus that is widely distributed throughout the temperate parts of the Northern Hemisphere. The eight British species have a slightly southerly bias: there are only five in Scotland and none at all in the Northern Isles (Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland.) Some are yellow and live entirely in the soil, others are jet black and forage in files up trees for honeydew. Their colonies are often enormous, extending to tens of thousands, and they may have only one queen. In general Lasius are very skilled at making nests out of soil or wood pulp. Undoubtedly the most striking is the jet black, large-headed Lasius fuliginosus which forages up tall trees from a carton nest in a rotting stump. It occurs sporadically in southern England. The queens are not much bigger than the workers and are unable to found colonies alone; they parasitize Lasius umbratus and other species as a first stage in colony formation. Lasius umbratus also has small queens and seems to be an obligate social parasite of Lasius niger. It is not often seen above ground, as its name implies, but is said to accompany Lasius fuliginosus up trees from mixed nests. Lasius brunneus, too, nests in old trees, usually oak, in open country; it has a curious distribution in the south Midlands, in part of which it has taken to entering the timber of buildings. Lasius alienus, a small, brown species, lives in subsurface galleries in the warm soils of heathland, limestone or chalk; it ejects the excavated soil to form characteristic craters in spring. Very common in Europe it extends like Tetramorium caespitum into Ireland and Scotland along the coasts. The behaviour of this ant seems to vary geographically: thus in England it rarely ascends into bushes, as it does in the Mediterranean area, but in America it lives in woodland. Lasius flavus is even more confined to the soil and in many parts of western Europe it builds large mounds of soil which are permanently covered with vegetation and which become a conspicuous feature of the landscape in areas of uncultivated grassland. It ranges throughout the British Isles except for parts of northern Scotland and Ireland. In many places, however, it is unable to form mounds: on steep slopes, in areas of high rainfall, in dry sandy soil or in cultivated grassland.

One of the most commonly encountered ants is Lasius niger. It is widely distributed throughout the British Isles but appears to be absent from some places in Ireland and Scotland. Bushy scrubland and gardens or wet places are its favourite habitats and it inhabits grassland only when stones or the mounds of Lasius flavus, which is a much more skilful builder, are available for it to nest in.

Formica is a genus of big, long-legged ants that spend their foraging lives in shrubs and trees and may build large mound nests of plant debris, although some only excavate galleries and chambers in the soil. It is widely distributed throughout the cooler parts of the Northern Hemisphere. There are eleven species in this country, nine in southern England, five in northern England, six in Scotland, five in Wales and three in Ireland. It thus shows a considerable southern bias.

The simplest Formica species are Formica fusca and Formica lemani. Both are black, have relatively small colonies and live in simple excavated nests in soil. They have strong workers that hunt and forage in bushes alone and are capable of carrying large prey back to the nest. These two species differ in several small ways; Formica fusca is less hairy, has up to half its pupae bare and is said to have fewer queens; it seems to be absent from all of Scotland except the Western Isles. Formica lemani occurs farther north than Formica fusca and is the only Formica in the Northern Isles. Both the species are common and widespread wherever they occur and in areas where they overlap Formica lemani tends to live in the cooler zones with the more northerly aspect.

There are also a number of rare Formica in this country, allied to Formica fusca; Formica cunicularia occurs in England and is slightly browner and hairier than fusca and often collects some plant material to make a small mound nest; Formica rufibarbis is quite reddish and very local. These are both common on the mainland of Europe. Formica transkaucasica, a jet black and shiny ant, is very rare, even in the south, but extends widely into Asia and is said to be the species which lives highest in the Himalayas. In England it is a specialist bog liver and covers its nests with small domes of cut grass, often on the tops of Molinia tussocks. Formica sanguinea is a large, red ant allied to the wood ants and has the habit of collecting the pupae of Formica fusca; many of these are eaten but some hatch out and the fusca workers stay on in the sanguinea nests, co-operating in the nest work; they have misleadingly been called ‘slaves’. The queens enter Formicafusca nests and replace the normal queen, thus living temporarily as social parasites. Formica sanguinea is widely but patchily distributed in the British Isles; it occurs in Scotland and southern England but not in northern England, Wales or Ireland. Formica exsecta is a small wood ant with a distribution like that of Formica sanguinea; it can be recognized by the cut-out scale and back of the head and by the fact that it builds mounds of vegetation in scrub and heath that are never very large and are really not much more than thatched soil mounds.

Finally in this cursory survey come the spectacular wood ants, well known for making huge mounds of vegetation debris with tracks to and up large forest trees on which they hunt for food. All have good sight and are expert with jets of formic acid which they can shoot several centimetres. There are three species. Formica rufa ranges over most of eastern and western England but is rare in the north and absent in Scotland and Ireland. Formica lugubris by contrast ranges from Wales and Ireland through northern England to Scotland, where it is widespread in the Highlands but apparently not in the Lowlands. The third, Formica aquilonia, is almost confined to the Scottish Highlands but has been recorded from one place in Ulster. It is an inhabitant of northern Europe and the High Alps. The differences in ecology between these species, so far as they are known, will be discussed later. On the European mainland there are two other species; one, Formicapolyctena, is very like rufa but has many more queens. Another, Formica pratensis, is less wood-bound than rufa and lives in meadows and roadsides, where it makes rather small nests. In central southern England it has recently been extinguished by suburban development.

The sub-family Dolichoderinae is represented only by the species Tapinoma erraticum, an active small, black ant with many queens in its colonies. This species makes nests in heathland; they are a mere 10 cm across and are covered with, and in part constructed of, vegetable debris. The ants seem always to be moving from one to another during the summer. Though widely distributed in Europe this species is confined to the central south of this country.

SPECIES RICHNESS

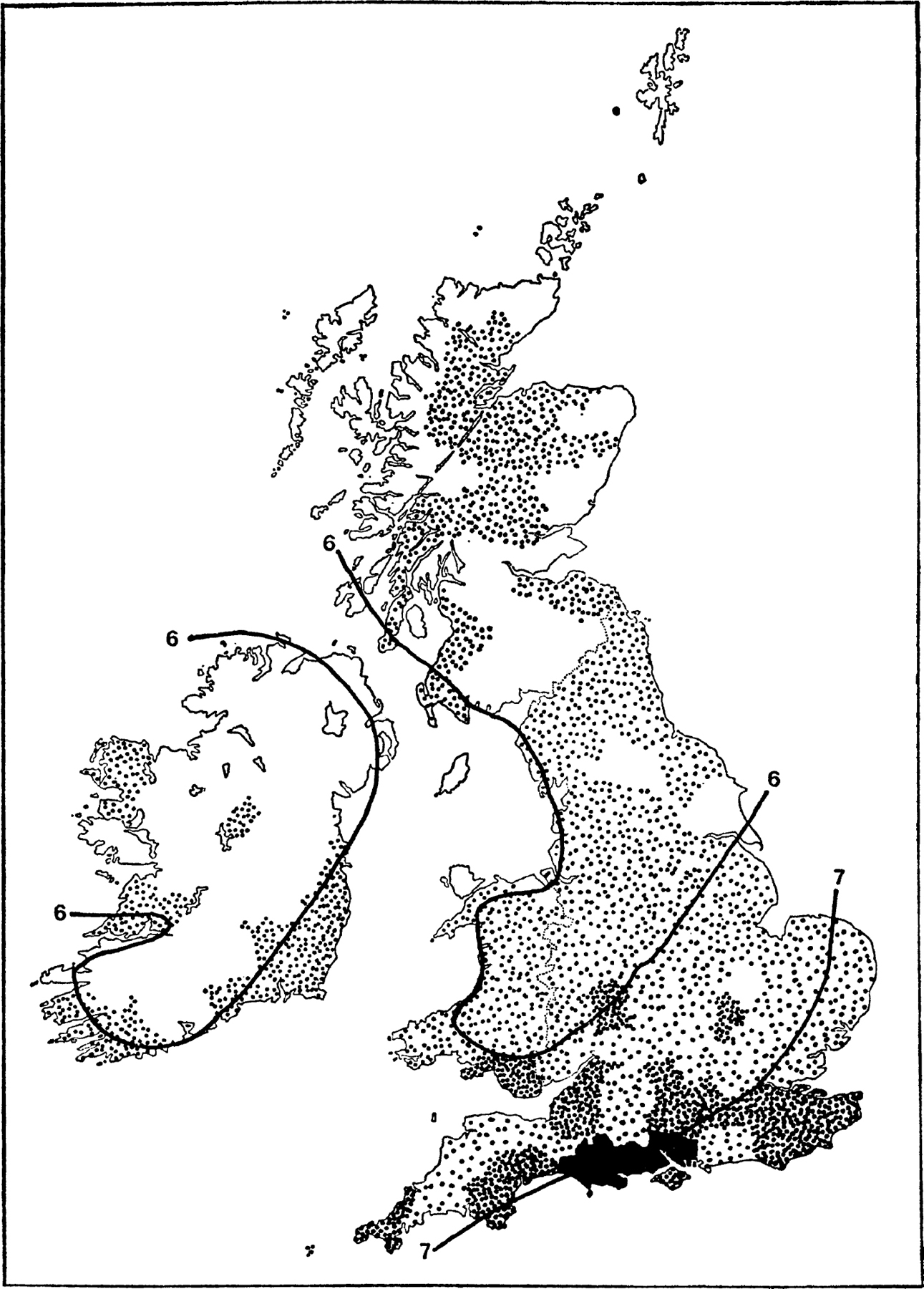

It is quite obvious from what has been said that the south is richer in species than the north. To be precise, of the 42 so far found in the British Isles, 33 occur in Dorset, 31 in Hampshire, 29 in Surrey, 27 in the Isle of Wight, 26 in East Kent and South Devon and 24 in Berkshire (see fig. 8). The regional divisions into which the Watsonian system groups its vice-counties show that Channel has 37, Thames 31 and Severn only 25 species. South Wales (24), Anglia (23), Trent (20), North Wales (18), and Lakes (18) come next. Not far behind are Humber (16), Mersey (15), Tyne (14) and the Scottish Lowlands West and East (14). The number rises to 15 in the West Highlands and 16 in the Eastern Highlands but drops again to 14 in the Northern Highlands. There are only 4 species in the Northern Isles. In Ireland, Leinster (18) and Munster (17) are twice as rich as Ulster (9); Connaught with 14 is intermediate.

This southerly tendency can be seen in ant distribution over the whole world. The humid Tropics have by far the greatest number. No doubt temperature is the most important single factor in this but rainfall, soil type, vegetation and humidity are subsidiary and of course highly interrelated. In this country the temperature of the soil where the ants live is probably more important than the air temperature and ant distribution is strongly influenced by the hours of sunshine in spring; this can be seen very clearly from fig. 8 in which the hours of sunshine in May have been plotted over the number of species per vice-county.

FIG. 8. The number of species of ant per vice-county and the zones where daily sunlight in May averages 6 to 7 hours. Black: over 30 species; densely dotted: over 20; lightly dotted: over 10; blank: between 1 and 10. The information on ants was obtained from the Transactions of the Society for British Entomology, Volume 16, Part 3, pages 93–121, Collingwood, C. A. and Barrett, K. E. J. The information on sunlight is from the Climatological Atlas of the British Isles, published by H.M.S.O. in 1952.

CHAPTER 4

FEEDING

EARLY ants lived on soil insects and this is still true of some primitive Ponerines. As simple predators ants were rather a long way from the primary source of food, the green plant, and their scope for population growth and spread and evolution was limited. The use of plant carbohydrates for energy, saving protein-rich foods, cannot have been long delayed as nectar-gathering is well established in the other primitive branch, the Myrmeciinae. Nectar is the common source of sugar in nature but other sources such as honeydew and fruit, both of which are quite easily recognized from their sugar and organic acid content, are more often used by ants. Seeds, though they are a very valuable source of food, are not eaten much, perhaps because their nutritive value is less easily recognized; they are, after all, covered in a tough skin. Fungi also have food value but are hardly used at all, though some of their threads which enter nest cavities from the surrounding wood or soil or which grow on their rubbish heaps may be cut and eaten. Only one group of ants, in tropical America, eat fungi regularly and systematically and these are cultivated in the nest and fed on vegetation which the ants collect regularly.