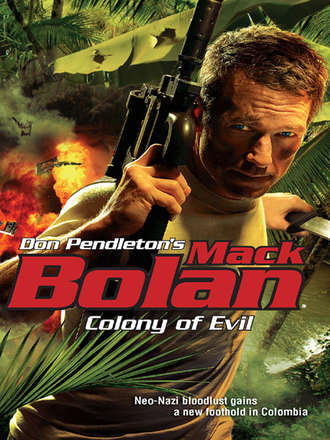

Colony Of Evil

Полная версия

Colony Of Evil

Жанр: приключениязарубежные приключенияисторическая литературасовременная зарубежная литературакниги о приключенияхсерьезное чтениеоб истории серьезно

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2019

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу