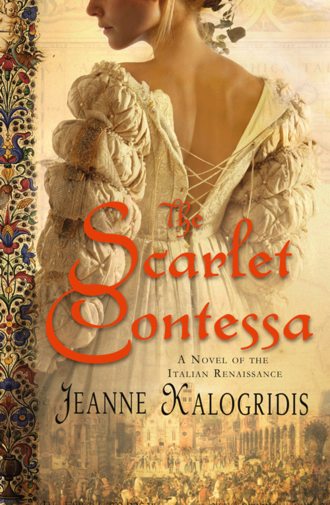

The Scarlet Contessa

Полная версия

The Scarlet Contessa

Жанр: книги о войнеисторическая литературасовременная зарубежная литературасерьезное чтениеоб истории серьезно

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2018

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу