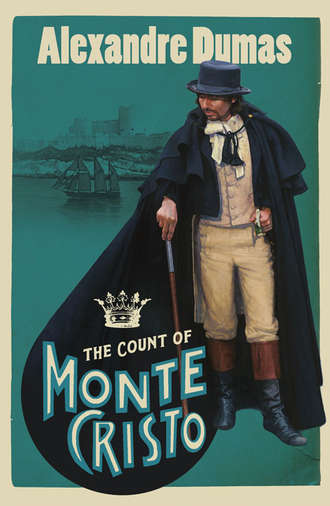

The Count of Monte Cristo

Полная версия

The Count of Monte Cristo

Жанр: историческая литературасовременная зарубежная литератураклассическая прозасерьезное чтениеоб истории серьезно

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2018

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу