Полная версия

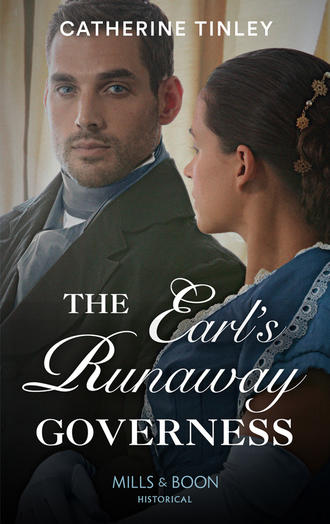

The Earl's Runaway Governess

Who knew living with an earl...

...would lead to such temptation?

Marianne Grant’s new identity as a governess is meant to keep her safe. But then she meets her new employer, Ash, Earl of Kingswood, and she immediately knows his handsome good looks are a danger of their own! Brusque on first meeting, Ash quickly shows his compassionate side. Yet Marianne doesn’t dare reveal the truth! Unless Ash really could be the safe haven she’s been looking for...

CATHERINE TINLEY has loved reading and writing since childhood, and has a particular fondness for love, romance and happy endings. She lives in Ireland with her husband, children, dog and kitten, and can be reached at catherinetinley.com, as well as through Facebook and @CatherineTinley on Twitter.

Also by Catherine Tinley

The Chadcombe Marriages miniseries

Waltzing with the Earl

The Captain’s Disgraced Lady

The Makings of a Lady

Discover more at millsandboon.co.uk.

The Earl’s Runaway Governess

Catherine Tinley

www.millsandboon.co.uk

ISBN: 978-1-474-08889-3

THE EARL’S RUNAWAY GOVERNESS

© 2019 Catherine Tinley

Published in Great Britain 2019

by Mills & Boon, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London, SE1 9GF

All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition is published by arrangement with Harlequin Books S.A.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, locations and incidents are purely fictional and bear no relationship to any real life individuals, living or dead, or to any actual places, business establishments, locations, events or incidents. Any resemblance is entirely coincidental.

By payment of the required fees, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right and licence to download and install this e-book on your personal computer, tablet computer, smart phone or other electronic reading device only (each a “Licensed Device”) and to access, display and read the text of this e-book on-screen on your Licensed Device. Except to the extent any of these acts shall be permitted pursuant to any mandatory provision of applicable law but no further, no part of this e-book or its text or images may be reproduced, transmitted, distributed, translated, converted or adapted for use on another file format, communicated to the public, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of publisher.

® and ™ are trademarks owned and used by the trademark owner and/or its licensee. Trademarks marked with ® are registered with the United Kingdom Patent Office and/or the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market and in other countries.

www.millsandboon.co.uk

To all my women friends—colleagues and school friends, college and GAA pals. And to the activists, campaigners and supporters in my life.

You are my sister writers, maternity co-campaigners, repealers and WHO Code supporters.

I feel your support in Women Aloud, the Unlaced Harpies, branch and regional volunteers, conference organisers and maternal mental health champions.

I salute you all.

Contents

Cover

Back Cover Text

About the Author

Booklist

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Epilogue

Extract

About the Publisher

Chapter One

Cambridgeshire, England, January 1810

Marianne tiptoed along the landing towards the servants’ staircase as quietly as she could manage. How different everything looked at night! A sliver of silver moonlight from the only window pierced the curtains, pointing at her. Look! it seemed to say. She is trying to escape!

Her skirts whispered as she moved through the darkness and her cloak billowed behind her like a black cloud. The creak of a floorboard under her feet sounded unnaturally loud, and she had to be careful not to allow her bandboxes to crash against the walls or the furniture. Shadows, unfamiliar and darkly threatening, loomed all around her, growing and shrinking ominously as she passed, her small candle gripped tightly in her right hand.

Downstairs a window rattled in a sudden gust of wind, and in the distance a vixen called mournfully. The candle flickered briefly as she reached the end of the landing, sending shadows scuttling and then reforming all around her.

She paused, listening for any sound, any indication that someone might have heard her.

Nothing.

Her heart was pounding—so much so that it was hard to hear anything above the din of her own blood rushing rhythmically through her body. Her mouth was dry and her palms sticky with fear. But she must not tarry! The longer she delayed, the greater the chance of being discovered.

Raising her candle, she carefully lifted the latch on the door to the back staircase. It gave way with a complaining click and Marianne bit her lip. She moved inside in a swish of silk and closed the door behind her.

She released her breath. Her first task was accomplished safely. Now for the next part.

She stepped down the stone stairs, her stout walking boots making a clatter that sounded thunderous to her ears. But with a closed door behind her hopefully it would not be loud enough to awaken anyone.

Reaching the bottom, she scuttled along the narrow passageway until she reached the chamber that the housekeeper shared with her daughter. The door was ajar, as arranged, and as she reached it Mrs Bailey opened it wide and bustled her inside, closing it securely behind her.

‘Oh, Miss Marianne! I never thought to see this day!’ Jane, the housekeeper’s daughter—Marianne’s personal maid—was sniffling into a handkerchief.

‘Hush now, Jane!’ Mrs Bailey admonished her daughter, though she herself also looked distressed.

Marianne set the candle down and touched the girl’s hand to soften her mother’s words. ‘We talked about this. You know it is for the best, Jane.’

They spoke in whispers, conscious that the housemaids were asleep in the chambers on either side. ‘But surely I should at least come with you?’ Jane protested.

Moved, Marianne enveloped her in a brief hug. ‘I love it that you would be willing to do so, but we all know there is no sense in it. Your place is here with your mother.’

Mrs Bailey, despite her stoicism, wiped away a tear. ‘Your own poor mother would break her heart if she knew you were running away from home, miss!’

Marianne felt the familiar pain stab through her. Mama and Papa had died over six months ago, yet she felt their absence still. Every waking moment.

‘Mama would want me to be safe, and I am no longer safe here.’ Even talking about it caused a wave of fear to flood through her.

‘I know, Miss Grant. It is best that you go.’ Mrs Bailey shook her head grimly. ‘Now, what have you packed?’

Marianne indicated the bandboxes in her left hand. ‘I fitted in as much as I could. My other black dress, two clean shifts, slippers, my reticule and my jean boots. A book. And Mama’s jewels.’ She lifted her chin. ‘I refuse to leave them here for him!’

‘They belong to you, miss. That was clear from the will, so they say. And when your parents made Master Henry your guardian they believed it was for the best.’

‘I know.’

Mama and Papa had refused to accept the truth—that Henry had no kindness in him, no sense of right and wrong. They would never knowingly have placed her in danger.

‘He is your brother, after all.’

‘My stepbrother.’ That had never seemed so important. ‘You know my real father died when I was a baby.’

Mrs Bailey acknowledged this with a nod. ‘The master and mistress were good for each other. Both widowed, both with a child to rear. It seemed a good marriage.’ She hesitated for a moment. ‘I have often wondered,’ she confessed, ‘if losing his own mother so young changed Master Henry.’

Marianne had no time to consider this. ‘He is who he is. I only know that I must escape before he...harms me.’

‘Of course you must.’

Unspoken between them was the fact that Mrs Bailey had rescued Marianne when Henry had cornered her a few hours earlier, in her chamber. He had been drunk, of course, but his unnatural interest in his stepsister was of long standing.

Marianne had been keenly aware of how the servants had kept her safe these past months, ensuring that Henry had no opportunity to be alone with her. Until today nothing had ever been said, but the butler had instructed the second footman to fit a new lock to Marianne’s chamber door just last week. Behind the locked door she had been able to relax a little.

Until tonight, when he had lain in wait for her within her own chamber.

Believing Henry to be still drinking with his raucous friends, in what had been her mother’s favourite drawing room, Marianne had hurried upstairs to seek the sanctuary of her room. Sighing with relief, she had closed her door and turned the key, only to hear him murmur silkily, ‘Good evening, my dear Marianne.’

She had whirled round to see him lying on her bed, his cravat loosened and a predatory look in his eye. Her mind had frozen for a second, and then wordlessly she had turned back to the door and unlocked it.

Before she had been able to open it properly he had been upon her, grabbing her from behind and muttering unspeakable things in her ear. Her shriek had not been loud enough to be heard in other parts of the house, but luckily Mrs Bailey had been nearby and had bravely intervened.

‘Oh, sir!’ she had said, bustling into the room. Pretending not to notice Marianne’s distress, or the position of Henry’s hands, she had gone on, with mock distress, ‘One of your friends has been violently sick and they are all requesting your presence.’

‘Damn and blast it!’

Henry had released her and stomped off, but not without a last look at Marianne. I shall win, it had promised. You cannot escape me for ever.

Mrs Bailey had stayed to soothe and calm Marianne. ‘Oh, my poor dear girl! That he would do such a thing!’

‘Please go—do not draw his anger,’ Marianne had urged, though her whole body had been shaking. ‘If the mess is not cleaned up quickly who knows what he will do!’

‘The footmen are already cleaning it,’ the housekeeper had reassured her. ‘My maids will not serve them in the evenings.’

They both knew why. The maids had also experienced the licentious behaviour of Henry and his drunken friends.

During the day their behaviour was rowdy, but they were usually reasonably restrained. In the evenings, however, fuelled by port and brandy, they became increasingly vulgar, ribald and uninhibited. And the entire household suffered as a result.

Marianne, pleading the conventions of mourning, had always avoided the ordeal of eating with them, choosing instead to consume a simple dinner each evening in the smaller dining room. She barely knew who was here this time—apart from his two closest friends, Henry’s guests were different for each house party.

Oh, their hairstyles and clothes were more or less the same—they were all ‘men of fashion,’ who spent their wealth on coats by Weston or Stultz, boots by Hoby and waistcoats by whichever master tailor was in fashion at that precise moment. Their behaviour, too, was more or less the same—arrogance born of entitlement and the belief that they could do whatever they wished, particularly to defenceless women. Including, it seemed, Marianne herself.

Knowing he would be criticised by society if he continued his customary carousing in public too soon after the tragic deaths of his father and stepmother, Henry had told Marianne that he had hit on the ‘genius notion’ of inviting all his friends for a series of house parties. Every few weeks, her home had been invaded by large groups of young men. They stayed for five or six nights each time and were up for every kind of lark.

The housemaids had learned to be wary of them, and Mrs Bailey had hired three older women to serve them, keeping Jane and the other young housemaids as safe as she could. Some of the servants—maids and footmen—had left already, to take up positions elsewhere. Very few long-serving staff remained—chief among them Mrs Bailey and Jane. Mrs Bailey had expressed the hope that once their year of mourning was completed, in March, Henry would return to his preference of living in the capital, and they would again have peace.

His attempt to assault Marianne herself this evening had changed everything.

While the behaviour of Henry and his friends had been gradually worsening, last night’s incident had been different. It had not been simply a lewd comment or a clumsy attempt to embrace a chambermaid. Henry had dark intentions, and Marianne now knew for sure that she was in danger. Running away was her only option. Mrs Bailey agreed.

‘Here is the direction for the registry I told you about.’ The housekeeper pressed a note into Marianne’s hand. ‘I have heard that they will place people who come without references. Lord knows we may need it ourselves before long.’

‘Thank you.’ Marianne secreted the note in her pocket, where her meagre purse also rested.

Although she had never wanted for food, new clothes or trinkets, and had a generous allowance, nevertheless she did not normally need access to much cash. This was an unusual and urgent situation, so she would have to make do with the pin money she’d had in her room. She drew her cloak around her and picked up her bandboxes again, this time hefting one in each hand.

‘Mr Harris will meet you at the gates.’ The housekeeper named one of the tenant farmers. ‘He will take you in his cart as far as the Hawk and Hound, where you can catch the stage at five in the morning. It comes through Cambridge from Ely and you will be in London by nightfall. I’ve also written down the names of two respectable inns. Hopefully one of them will have a room free. Stay there until you find a situation as a governess.’ She gripped Marianne’s hand. ‘I am so sorry that you have to leave your home, miss. Please take care of yourself.’

‘I will.’

Marianne nodded confidently, as if she knew what she was doing. But as she walked up the drive in darkness, away from the only home she had ever known, her heart sank.

How on earth am I to manage? she wondered. For I have never before had to take care of myself!

Grimly, she considered her situation. She had been gently reared, and could play the harp and sing, sketch reasonably well and set a neat stitch. She had been bookish and adept at her lessons when she was younger.

But she had no idea how to buy a ticket for the stagecoach, or wash clothes, or manage money.

She had also never been in a public place unaccompanied before. Mama had always been with her, or her governess, or occasionally a personal maid. But those days were gone. She must learn to dress by herself now, and mend her own clothing, and dress her own hair. And somehow she must keep herself safe in the hell that was London.

London! She knew little of the capital—had never visited the place. But in her mind it was associated with all kinds of vice. London was where Henry lived. London was where his arrogant, lecherous friends lived. London, she had come to understand, was a place overrun with wicked young men, drinking and vomiting and carousing their way through the streets, gambling dens and gin salons.

Mama and Papa had hated to visit the place, and had always exclaimed with relief when they’d returned home to country air and plain cooking. They had never taken her with them, leaving her safely in the care of her nurse or governess, and Marianne had never objected. Even as a child she had understood that London was a Bad Place, and she had been puzzled by Henry’s excitement at going there.

When he had become old enough he had insisted on having lodgings of his own in the city, and with reluctance Papa had given in to his son’s demands. Henry had moved to London, rarely coming home to visit, and everyone at home had breathed a little easier.

And now here she was, leaving home in the middle of a cold January night, with little money, no chaperone, and no notion of how she was going to manage. And she was choosing to go to London, of all places.

She stifled a hysterical giggle. Strangely, the absurdity of it all had cheered her up. That she could laugh at such a moment!

She lifted her chin, squared her shoulders, and trudged on.

Netherton, Bedfordshire

William Ashington, known to his friends as Ash, rubbed his hands together to keep away the cold. The vicar’s words washed over him. ‘For as much as it hath pleased Almighty God in his great mercy to take unto himself the soul of our dear brother here departed: we therefore commit his body to the ground—earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust...’

Ash threw a handful of earth onto John’s coffin, feeling again the loss of the man who had been much more to him than a cousin. In truth John had been like a brother to him—at least until that summer when they had both turned eighteen. In recent years they had recovered something of an awkward friendship, but it had never been the same.

How could it?

He turned away as the service ended, accepting a few handshakes and murmuring appropriate responses to the expressions of sorrow being offered.

‘My Lord?’ It was the vicar. Ash started, realising the man was addressing him. Strange to think that because of John’s death he was now not simply Mr Ashington but the Earl of Kingswood.

‘Yes?’

The vicar shook his hand and thanked him for attending the service. ‘A funeral is always a sad occasion, but laying to rest such a young man is doubly sorrowful. Why, he was not much more than two and thirty!’

I know, thought Ash. For John and I are—were—almost the same age.

‘And to think of his widow and daughter, now left alone in the world...’ The vicar sighed, then looked at Ash intently. ‘Lord Kingswood—er...the previous Lord Kingswood spoke about them often to me in his final weeks.’

‘Indeed.’ The last person Ash wished to think about was John’s widow. Thank goodness women did not attend funerals.

‘He also spoke about you.’ The vicar’s warm brown eyes bored into Ash’s. ‘I think he regretted the distance between you.’

Ash was feeling extremely uncomfortable. He was unaccustomed to discussing his personal affairs with someone he had just met. In truth, he was unaccustomed to discussing his personal affairs with anyone. He preferred it that way.

Adopting his usual defence in such moments, he maintained an even expression and said nothing.

The vicar made a few more general comments and Ash listened politely. He thanked the man and turned away to where his coachman, Tully, waited with the carriage. If he left now he could be back in London by tonight.

‘Er...’

The vicar. Again.

‘Yes?’ Ash’s patience was beginning to wear thin, but he forced himself to maintain a courteous expression.

‘I was asked to pass this to you.’ He offered Ash a sealed note.

Ash frowned but took the paper. Opening it, he ran his eyes over the contents.

‘Confound it!’ he snapped, causing the vicar to raise an eyebrow. ‘I am requested to go to the house after the funeral. By the family lawyer.’

The vicar looked bewildered at his reaction to what must seem a perfectly reasonable request. They were literally standing together at the Fourth Earl of Kingswood’s funeral, and Ash was now the Fifth Earl.

But he had never expected to accede to the title.

Why, John had been only thirty-two, with plenty of time to sire a son with Fanny. Everyone—including Ash—had assumed that John would eventually have sons, and that he—Ash—would never have to worry about the responsibilities John had carried for so long.

Ash debated it in his mind. Could he ignore the note and leave immediately for London, as planned? He could ask the lawyer to see him there. No. It would look churlish and impolite. Damn. He would have to comply as a courtesy. Which meant possibly seeing her again.

Fanny. John’s wife—John’s widow, he corrected himself. After all these years of successfully avoiding her.

Placing his hat firmly on his head, he bade farewell to the vicar and made for his carriage. If he must face this ordeal, better to get it over with.

Chapter Two

Marianne reminded herself to breathe. Her shoulders were tense and she could feel fear prick her spine. She had paid the fee and entered her name into the registry book at the office recommended by Mrs Bailey, and now she waited.

Well, she acknowledged, not her actual name. Her made-up name.

She had decided during the long journey to London that she must not go by her usual name, for fear Henry might look for her. She would use her father’s surname—her real father—as it would give her comfort, and she was confident Henry would not remember or recognise it.

After being known as Marianne Grant for most of her twenty years, she would now go back to the surname she had been given at birth—Bolton. Charles Bolton had given her her dark brown eyes, her dark hair and, according to Mama, her placid nature. The Grants were altogether more fiery.

She was seated in an austere room with a dozen other would-be servants, all patiently awaiting their turn to be called. Among the would-be grooms, scullery maids and footmen she had espied two other young ladies, respectably dressed, who might also be seeking employment as governesses. She had exchanged polite smiles with both of them, but no one had initiated conversation.