Полная версия

Echoes of old Lancashire

Some Lancashire Centenarians

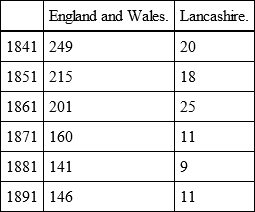

According to the census of 1891 there were 146 persons enumerated who were returned as being more than 100 years of age. Eleven of these were resident in Lancashire. It may be interesting to compare this with the statements in some of the preceding census reports. Arranged in tabular form, the following results are seen: —

Centenarians returned at each successive census.

In Lancashire, it will be noticed, there has been a marked tendency towards the diminution of reputed centenarians. The general consent of mankind seems to have fixed upon a hundred years as almost the outside limit for the duration of human life. The Hebrews and the Chinese are agreed in this. The Celestials have a quaint way of dividing a life into cycles. From birth to 10 years of age is the opening degree; at 20, youth expired; 30, strength and marriage; 40, officially apt; 50, error knowing; 60, cycle closing; 70, rare bird of age; 80, rusty visage; 90, delayed; 100, age’s extremity. Far more claims to great longevity are made than can be sustained by reasonable evidence, and it should not be forgotten that the burden of proof belongs to those who make these statements. The bulk of mankind do not exceed, and many of them never attain, the Psalmist’s term of three score years and ten, and it is only reasonable that those who claim for themselves or protégés an existence of five or six score should be required to produce adequate evidence in support of their allegations. Curiously enough until the second half of the present century statements of extreme old age appear to have been accepted without doubt or inquiry. In the census report of 1851 a sceptical note was struck, and since then the late Sir G. C. Lewis and Mr. W. J. Thoms – especially the latter – have done useful service by a persistent demand for evidence. Under investigation some cases have proved to be impostures, and others mistakes and self-deceptions.

The historian of the county of Lancaster claims for Ormskirk parish the prevalence of an unusual degree of longevity. In the churchyard there are gravestones over four venerable parishioners, which record that the first of them died at the advanced age of 94, the second at the age of 102, the third at the age of 104, and the fourth at the age of 106 years. Many centenarians, real or supposed, have been connected with Lancashire, and it is more than probable that a rigid investigation at the time would greatly have reduced the number. They are here presented in chronological order, and have been derived from a variety of sources: —

1668. – Dr. Martin Lister, writing to the Royal Society, says that John Sagar, of Burnley, died about the year 1668, “and was of the age (as is reported) of 112.”

1700. – “Here resteth the bodie of James Cockerell, the elder, of Bolton, who departed this lyfe in the one hundredth and sixthe yeare of his age, and was interred here the seventh day of March, 1700” (Whittle’s “Bolton,” p. 429).

1727. – In the diary of William Blundell, of Crosby, under date 21st January, 1727, there is this entry: – “I went to Leverp: and made Major Broadnax a visit, he told me that in March next he will be 108 years of Aige, he has his memory perfectly well, and talks extreamly strongly and heartally without any seeming decay of his spirrits.” This, according to the Rev. T. E. Gibson, was “Colonel Robert Broadneux, at one time gentleman of the Bedchamber to Oliver Cromwell, and afterwards Lieut. – Col. in the Army of King William, died the following January, and was buried in St. Nicholas’ churchyard, Liverpool, where his memorial stone may still be seen. He is there credited with 109 years, which, according to the diarist’s account, is one too many.”

1731. – Timothy Coward, of Kendal, 114.

1735. – James Wilson, of Kendal, 100.

1736. – Roger Friers, of Kendal, 103.

1743. – Mr. Norman, of Manchester, 102.

1753. – Thomas Coward, of Kendal, 114. The following is an inscription on a tombstone in Disley Church: —

“Here Lyeth Interred the

Body of Joseph Watson, Buried

June the third, 1753,

Aged 104 years. He was

Park Keeper at Lyme more

than 64 years, and was ye first

that Perfected the Art of Driving

ye Stags. Here also Lyeth

the Body of Elizabeth his

wife Aged 94 years, to whom

He had been married 73 years.

Reader, take notice, the Longest

Life is Short.”

This Joseph Watson was born at Mossley Common, Leigh, Lancashire, in 1649. Watson was park-keeper to Mr. Peter Legh, of Lyme. About 1710, in consequence of a wager between his employer and Sir Roger Moston, Mr. Watson drove twelve brace of red deer from Lyme Park to Windsor Forest as a present for Queen Anne. He was a man of low stature, fresh complexion, and pleasant countenance. “He believed he had drunk a gallon of malt liquor a day, one day with another, for sixty years; he drank plentifully the latter part of his life, but no more than was agreeable to his constitution and a comfort to himself.” In his 103rd year he killed a buck in the hunting field. He was the father of the Rev. Joseph Watson, D.D., rector of St. Stephens, Wallbrook, London.

1755. – Mr. Edward Stanley, of Preston, was buried in that town 4th January, 1755, at the reputed age of 103. He was one of the Stanleys of Bickerstaffe – the branch of the family that eventually succeeded to the Earldom of Derby. His father was Henry Stanley, the second son of Sir Edward Stanley, of Bickerstaffe.

1757. – James Wilson, of Kendal, 100.

1760. – Elizabeth Hilton, widow, of Liverpool, 121.

1761. – Isaac Duberdo, of Clitheroe, 108. Elizabeth Wilcock, of Lancaster, 104. John Williamson, of Pennybridge, 101. William Marsh, of Liverpool, 111, pavior.

1762. – Elizabeth Pearcy, of Elell, 104. Elizabeth Storey, of Garstang, 103.

1763. – Mr. Wickstead, of Wigan, 108, farmer. Thomas Jackson, of Pennybridge, 104. Mrs. Blakesley, of Prescot, 108. Mr. Osbaldeston, near Whaley, 115.

1764. – James Roberts, of Pennybridge, 113.

1765. – Mr. Glover, of Tarbuck, 104.

1767. – George Wilford, of Pennybridge, 100. William Rogers, of Pennybridge, 105. Thomas Johnson, of Newbiggin, 105.

1770. – Ellin Brandwood, Leigh, 102.

1771. – Nathaniel Wickfield, of Ladridge, 103. Mr. Fleming, of Liverpool, factor, 128. He left a son and a daughter each upwards of a hundred.

1772. – Mr. Jaspar Jenkins, whose death at Enfield in the 106th year of his age is recorded in the Gentleman’s Magazine for 1772, was formerly a merchant of Liverpool.

1778. – John Watson, Limehouse Park (of which he was keeper), 130. Mr. Husan, of Wigan, 109.

1779. – Susan Eveson, Simmondsone, near Burnley, 108.

1780. – William Ellis, of Liverpool, shoemaker, 131. He was seaman in the reign of Queen Anne, and a soldier in the reign of George I. Thomas Keggan, of Liverpool, 107.

1781. – Peter Linford, of Maghall, Liverpool, 107.

1782. – Henry Lord, of Carr, in the Forest of Rossendale, 106. He was a soldier in the service of Queen Anne. Martha Ramscar, of Stockport, 106.

1783. – Thomas Poxton, of Preston, 108. He was formerly a quack doctor. He attended Ormskirk market, twenty miles distant, constantly till within a few years of his death; was healthy and vigorous to the last, and was generally known by the name of Mad Roger. William Briscoe, Park Gate, 101. Mrs. Holmes, Liverpool, 114. She was married at 48 years of age, and had six children.

1784. – George Harding, Manchester, 111. He served as a private soldier in the reigns of Queen Anne, George I., and George II. Matthew Jackson, of Hawkshead, 100. He was married about eighteen months before his death.

1786. – Elizabeth Curril, 100, Liverpool. Jonathan Ridgeway, of Manchester, 100.

1787. – Mrs. Bailey, of Liverpool, 105. She retained her senses to the last, was never bled or took medicine in her life, and read without spectacles. Her mother lived to the age of 116.

1790. – Jane Monks, Leigh, 104. She retained all her faculties till within a few hours of her death, and except for the last five years earned her living by winding yarn. James Swarberick, Nateby, 102. Sarah Sherdley, Maghull, 105. She was an idiot from her birth.

1791. – Jane Gosnal, 104, Liverpool. Frances Crossley, 109, Rochdale, widow.

1793. – Mrs. Boardman, 103, Manchester, widow.

1794. – William Clayton, Livesey, Blackburn, 100. The summer before his death he was able to join in the harvest work, about which time he had a visit from a man of the same age who then lived about ten miles distant, and who said he had walked the whole way. Elizabeth Hayes, Park Lane, Liverpool, 110. Mrs. Seal, 101, an inmate of an almshouse in Bury. In the earlier part of her life she was remarkable for her industry, but had been many years bedridden, and supported principally by parish relief.

1795. – Mrs. Hunter, 115, Liverpool. Roger Pye, 102, Liverpool. Christian Marshall died at Overton, near Lancaster, aged 101.

1796. – Anne Bickersteth, 103, Barton-in-Kendal, widow of Mr. Bickersteth, surgeon of that place. She retained her bodily and mental faculties till her death, and walked downstairs from her bedroom to her parlour the day she died. William Windness, 110, Garstang. Anne Prigg, 104, Bury.

1797. – Jane Stephenson, 117, Poulton-in-the-Fylde.

1798. – Richard Hamer, Hunt Fold, Lancaster, 102.

1799. – Mrs. Owen, 107, Liverpool. John M’Kee, 100, Liverpool, joiner. Mary Jones, 105, Liverpool, workhouse. Margaret Macaulay, of Manchester, aged 101. She was a well-known beggar.

1807. – Mrs. Alice Longworth, Blackburn, aged 109. She retained the use of her faculties till her last illness, and never wore spectacles. Her youngest daughter is upwards of 60. – (Athenæum, September, 1807).

1808. – Mary Ralphson, died at Liverpool, 27th June, 1808, aged 110. She was born January 1st, 1698, O.S., at Lochaber, in Scotland. Her husband, Ralph Ralphson, was a private in the Duke of Cumberland’s army. Following the troops, she attended her husband in several engagements in England and Scotland. At the battle of Dettingen she equipped herself in the uniform and accoutrements of a wounded dragoon who fell by her side, and, mounting his charger, regained the retreating army, in which she found her husband, and returned with him to England. In his after campaigns she closely followed him like another “Mother Ross,” though perhaps with less courage, and more discretion. In her late years she was supported by some benevolent ladies of Liverpool. A print of her was published in April, 1807, when she was resident in Kent Street, Liverpool.

1808. – There is a print without date of “David Stewart Salmon, aged 105, the legal Father of two Indian Princes of the Wabee Tribe in America. A resident of Cable Street, Liverpool. After serving his King and Country upwards, of sixty years six months and five days of which time was spent without ever leaving his Majesty’s Service, is now allowed 2s. 6d. per week from the Parish of Liverpool. He is the last survivor of the Crew of the Centurion when commanded by Commodore Anson, with whom he sail’d round the World.”

1808. – Mr. Joe Rudd, writing from Wigan, June 10th, 1808, forwards the following contribution to Mr. Urban (Gentleman’s Magazine, vol. lxxviii., pt. ii., 576): – “I request you to record the following narrative of the longevity of one family in the town of Wigan, Lancashire, where Old Anne Glave died in The Scholes a few years since at the advanced age of 105. She was a woman well skilled in herbs, and obtained her livelihood by gathering them in their proper seasons. She retained her faculties till the last, and followed her trade of herb-gathering within a short time of her death. Anne was the daughter of Barnard Hartley, who lived 103 years, and lies buried in Wigan churchyard. Anne had several children, four of whom are now living at Wigan in good health, viz., Anne, aged 91; Catherine, aged 82; Sarah, 75; and Elizabeth, 72. Old Anne Glave buried her husband, Robert, at the age of 84. He was a fisherman, and famous for making rhymes.” Jemina Wilkinson, Blackpool, aged 106. She retained her senses, and was able to walk without assistance within a few hours of her death. – (Athenæum, October, 1808).

1809. – Mrs. Mary Leatherbarrow, of Hulme, died at the age of 106.

1817. – Catharine Prescott, who died in George Leigh Street, June 2nd, at the reputed age of 108, was a notable character in her day. It was said of her that she learned to read – and that without spectacles – partly at the Lancasterian School and partly at Bennet Street School after she had passed her hundredth year.

1818. – Mary Harrison, who, in 1818, was living at Bacup, was said to be 108 years old.

1826. – Mrs. Sarah Richardson, a widow, who resided at the Mount, Dickenson Street, died at the reputed age of 101. She was a native of Warrington, and her descendants numbered 153.

1841. – John Pollitt, aged 52, and George Pollitt, brothers, were interred at Rusholme Road Cemetery, November 16th. They were followed to the grave by their father, William Pollitt, of Dyche Street, who had attained the age of 104, accompanied by his great-great-grandson aged 21 years.

1848. – An old woman living in Burn Street, Chorlton-upon-Medlock, 110 years old, and in the possession of all her faculties. She perfectly recollected the coronation of George III., which took place when she was 24 years old.

1859. – Betty Roberts was said to be living in Liverpool in 1859, and her birth was asserted to have taken place at Northrop, in Flintshire, in 1749. Her son, aged 80, was living with her.

1877. – In 1877 there appeared a notice of John Hutton, who was born at Glasgow 18th August, 1777, and was apprenticed at Carlisle in 1793 as a handloom weaver, but came to Manchester in 1796, where he served the remainder of his apprenticeship, and was married in December, 1797, by Parson Brookes. He became an employé of the firm of Thomas Hoyle and Son, of Mayfield, and by his skill in mixing became of considerable importance. In particular, he had a secret for the preparation of China blue, which was entrusted to his son, who died at a good age, without having left a successor to the secret. Messrs. Hoyle’s chemist, it is said, who knew all about the theory of the dye, failed to get the exact tint that was requisite, and a joking suggestion was made to the old man that his services were still in demand. He took the observation seriously, proceeded to the dyehouse, where under his directions the brew was a conspicuous success. He was of medium size, cheerful temperament, and habits of great regularity. He took little interest in any matters outside the narrow limits of his household and the works. He was not a teetotaller, but was exceedingly sober and steady. He completed his hundredth year 18th August, 1877. His senses were somewhat dulled, and the arcus senilis was well marked. On his centenary he was photographed in a group with his daughter, grandson, great-grandson, and great-great-grandson. His fellows of the Mayfield Works entertained him at Worsley, and in a bath-chair he was enabled to enjoy the gardens.

1879. – Sarah Warburton, who died at Accrington in 1879, was reputed to have been born February 2nd, 1779. At the old folks’ tea-party during the Christmas before her death she received the prize of a new dress-piece for singing a song of her juvenile days!

1881. – The case of the “Crumpsall Centenarian” excited some interest in 1881. She died October 8th, 1881, and was reported to be in the 108th year of her age. Jane Pinkerton, whose maiden name was Fleming, according to the testimony of the entry in a family Bible, in which the names of her brothers and sisters were also entered, was born 16th June, 1774, within a few miles of Paisley, in Scotland. When she was a girl her father took his family to Ireland. She married James Pinkerton, a schoolmaster in the neighbourhood of Belfast, and at his death she came to reside with a married daughter at Lower Crumpsall. She is buried in the Wesleyan Cemetery, Cheetham Hill.

This list is not a complete one, and doubtless many additions, some in quite recent years, might be made to it. The reader will notice that with few exceptions, amongst which is the remarkable case of John Hutton – there is for the most part an entire absence of evidence. The ages stated have evidently been taken down from the statements of the old men and women, with little or no attempt to verify their correctness. It may be useful to cite two cases that were adequately investigated. The case of Miss Mary Billinge, of Liverpool, is instructive as showing the possibilities of error. She was said to have been 112 years old at the time of her death, 20th December, 1863, and a certificate of baptism was obtained which stated the birth of Mary Billinge, daughter of William Billinge and Lydia his wife, on the 24th May, 1751. It was known that she had a brother named William and a sister named Anne, who are buried at Everton. A reference to the registers showed that these were entered as the children of Charles and Margaret Billinge, and a further search revealed the name of Mary, born 6th November, 1772, and therefore only a little over 91 at the time of her death. The certificate relied upon to prove her centenarian age was that of an earlier Mary Billinge.

The other instance is that of Mrs. Martha Gardner, who died at 85, Grove Street, Liverpool, March 10th, 1881, at the age of 104. This will be best given in the words of Mr. W. J. Thoms, who, after the date of her death, says: – “Some two or three years ago Dr. Diamond kindly forwarded to me a photograph, taken shortly after the completion of her hundredth year, by Mr. Ferranti, of Liverpool. I afterwards received from two different sources evidences as to the birth of this very aged lady, whose father, a very eminent Liverpool merchant, has duly recorded in the family Bible the names, dates of birth, and names of godfathers and godmothers of his fourteen children, who were all baptised at home, but whose baptisms are duly entered in the register of baptisms of the Church of St. Peter, Liverpool. Mrs. Gardner having a great objection to being made the subject of newspaper notices or comments, I advisedly refrained from bringing her very exceptional age under the notice of your readers during her lifetime. I may add that she was a cousin of an early and valued contributor to Notes and Queries, the Rev. John Wilson, formerly president of Trinity College, Oxford, and on his death on July 10th, 1873, Mrs. Gardner took out letters of administration to his estate, and her correspondence, she being then in her 97th year, rather astonished the legal gentleman with whom she had to confer on that business.”

What was the First Book Printed in Manchester?

The answer to this question is not so obvious as might at first be expected. There were in the Lancashire of Elizabeth’s days two secret presses. From one there issued a number of Roman Catholic books. This was probably located at Lostock, the seat of the Andertons. The other was the wandering printing-press, which gave birth to the attacks of Martin Marprelate upon the Anglican Episcopate. This was seized by the Earl of Derby in Newton Lane, near Manchester. The printers thus apprehended were examined at Lambeth, 15th February, 1588, when Hodgkins and his assistants, Symms and Tomlyn, confessed that they had printed part of a book entitled, “More Work for the Cooper.” “They had printed thereof about six a quire of one side before they were apprehended.” The chief controller of the press, Waldegrave, escaped. In these poor persecuted printers we must recognise the proto-typographers of Manchester. No trace remains of “More Work for the Cooper.” The sheets that fell into the hands of the authorities do not appear to have been preserved. Putting aside the claims of this anti-prelatical treatise, we have to pass from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. Many tracts and books by local men, and relating to local affairs, were printed before 1719, but that appears to be the date of the first book printed in Manchester. The title page is here reproduced: – “Mathematical Lectures; being the first and second that were read to the Mathematical Society at Manchester. By the late ingenious Mathematician John Jackson. ‘Who can number the sands of the Sea, the drops of Rain, and the days of Eternity?’ – Eccles. i., 2. ‘He that telleth the number of the Stars and calleth them all by their Names.’ – Psalm cxlvii., 4. Manchester; printed by Roger Adams in the Parsonage, and sold by William Clayton, Bookseller, at the Conduit, 1719.” (Octavo.)

The claims of Jackson’s “Lectures” were stated by the present writer in Notes and Queries (see fourth series, iii., 97, and vii., 64), and in his “Handbook to the Public Libraries of Manchester and Salford.” Some further correspondence appeared in Local Gleanings (vol. i., p. 54), and an extract was given from one of William Ford’s catalogues, which, if accurate, would show that there was a local press at work in 1664. Ford has catalogued a book in this fashion: – “A Guide to Heaven from the Word; Good Counsel how to close savingly with Christ; Serious Questions for Morning and Evening; Rules for the due observance of the Lord’s Day. Manchester, printed at Smithy Door, 1664. 32mo.”

Apparently nothing could be clearer or less open to doubt. After a careful look out for the book, a copy has been secured, and is now in the Manchester Free Library. The title reads: – “A Guide to Heaven from the Word. Good counsel how to close savingly with Christ. Serious Questions for Morning and Evening; and rules for the due observation of the Lord’s Day. John 5, 39. Search the Scriptures. Manchester: Printed by T. Harper, Smithy Door.” (32 mo, pp. 100.) There is no date, but the name of Thomas Harper, printer, Smithy Door, may be read in the “Manchester Directory” for 1788, and the slightest examination of the “Guide to Heaven” will show that its typography belongs to that period. From whence, then, did Ford get the date of 1664? If we turn to the fly-leaf the mystery is explained, for on it we read, “Imprimatur, J. Hall, R.P.D. Lond. a Sac. Domest. April 14 1664.” The book, in fact, was first printed in London in 1664, and Thomas Harper, when issuing it afresh, reprinted the original imprimatur, which Ford then misconstrued into the date of the Manchester edition. The book is entered as Bamfield’s “Guide to Heaven” in Clavell’s “Catalogue,” and the publisher is there stated to be H. Brome. Either Francis or Thomas Bamfield may have been the author, but the former seems the more likely. Thomas Bampfield – so the name is usually spelled – was Speaker of Richard Cromwell’s Parliament of 1658, and he was a member of the Convention Parliament of 1660, and was the author of some treatises in the Sabbatarian controversy. Francis was a brother of Thomas, and also of Sir John Bamfield, and was educated at Wadham College, Oxford, where he graduated M.A. in 1638. He was ordained, but was ejected from the Church in 1662, and died minister of the Sabbatarian Church in Pinner’s Hall. He wrote in favour of the observation of the Saturday as the seventh day, and therefore real Sabbath, and whilst preaching to his congregation was arrested and imprisoned at Newgate, where he died 16th February, 1683-4. His earliest acknowledged writing was published in 1672, and relates to the Sabbath question.

The first book printed in Manchester, so far as the present evidence goes, was Jackson’s “Mathematical Lectures,” but it was the fruit of the second printing-press at work in the town.

Thomas Lurting: a Liverpool Worthy

Quakerism has a very extensive literature, and is especially rich in books of biography; which are not only of interest from a theological point, but are valuable for the incidental and sometimes unexpected light which they throw upon the history and customs of the past. One of the early Quaker autobiographies is that of Thomas Lurting, a Liverpool worthy, who has not hitherto been included by local writers in the list of Lancashire notables.

Thomas Lurting was born in 1629, and, in all probability, at Liverpool. The name is by no means a common one, but it is a well-known Liverpool name, and many references to its members will be found in Sir James Picton’s “Memorials and Records.”1 From 1580 to the close of the seventeenth century they appear to have been conspicuous citizens. John Lurting was a councillor and “Merchant ’Praiser” in 1580. A John Lurting was bailiff of the town in 1653; but three years earlier had so little reverence for civic dignity as to style one of the aldermen “a cheating rogue.”